I’ve come across this question more times than I can count: “If you had a million dollars to give away, who would you give it to?” And every time, I wonder why I would give it all away. If I’m being honest, I’d keep it. It’s not that I’m greedy, but I know exactly what I’d do with it. I’ve spent most of my life putting off dreams, setting aside passions, and delaying joy in the name of responsibility. That would change with a million dollars. It would let me breathe and stop merely getting by and begin living with a little more softness and space.

First, I would look after my family. I would pay off all of our debts, every last sen, until there would be no more worries about bills, school fees, or emergencies that come up out of the blue. I would put some of the money into investments, save some of it, and then I would finally let myself enjoy something I have always loved: books.

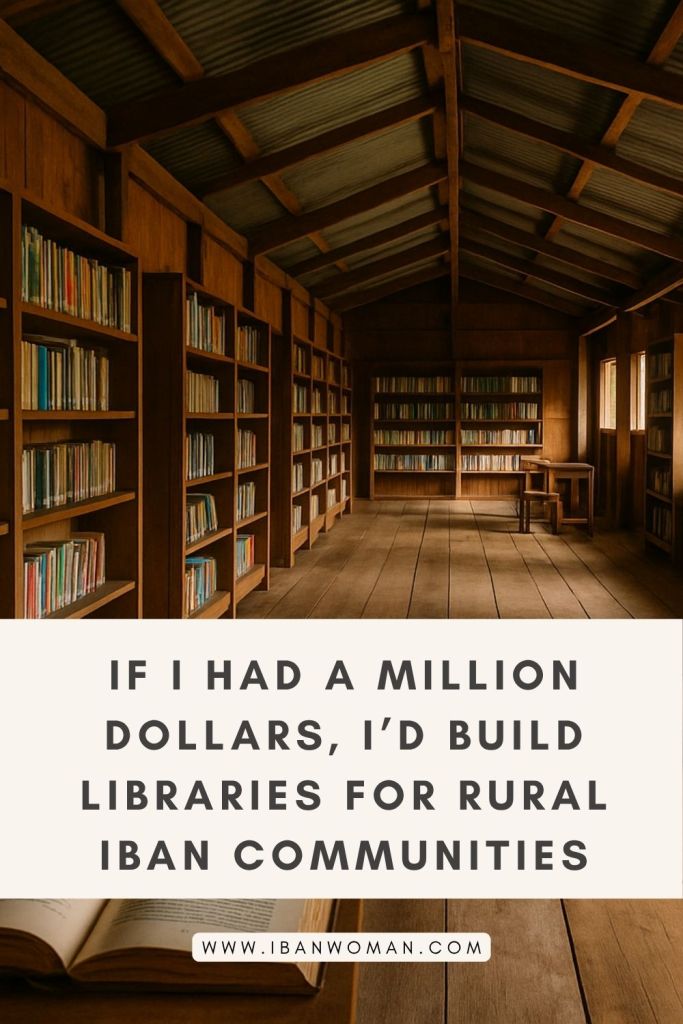

I’d buy all the books I’ve always wanted. These aren’t the ones found in chain stores, but the rare ones. The hard-to-find books that tell the history and tradition of my people. I’d look for heritage books published by the now-defunct Borneo Literature Bureau. These slim, worn books contain the voices of writers who wrote about us long before I was born. I’d buy the complete Encyclopedia of Iban Studies set from the Tun Jugah Foundation and every contemporary book that strives to record what we might forget. I wouldn’t hoard them, but I’d preserve these gems in my private collection. And I would keep them safe in a room with shelves and sunlight. A library for me and anyone else who needs to learn and remember where we came from.

Maybe that sounds selfish, but it’s a way for me to preserve my heritage, which is for the whole family and the generations after. But if I had to give it away, like if the million had to leave my hands and go to someone else, I wouldn’t give it away in cash. I’d use it to build something that would last and grow.

I’d set up a library. Perhaps more than one. In the interior of Sarawak, where villages are still without decent access to books, let alone libraries. Where stories are passed down through voices but never written. I’d create a place where kids could find books in their own language and where Iban stories are just as important as stories from other parts of the world. I’d build a place where books wouldn’t be locked behind glass but placed in the hands of the community to read and savor. And who knows, maybe a child who never saw herself reflected in school textbooks will see her village, her ancestors, and her identity printed on paper, validated in ink.

I’d make sure the internet actually works. I would stock not only novels and dictionaries but also materials that could broaden the mind, such as bilingual books, local folktales, science and art books, poetry, comics, storybooks for toddlers, and plenty of activity books. I’d make room for community events, nights of storytelling, and maybe even small poetry workshops in the future. The kind of space I never had when I was young.

To be honest, I wouldn’t give away a million dollars just to feel good about myself or tick a box labeled “generous.” I would use it to make something that is useful and necessary. I want to create one or more spaces where my Iban language can coexist with other languages. I want to help fund a place where the next generation won’t have to look so hard to find themselves.

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.