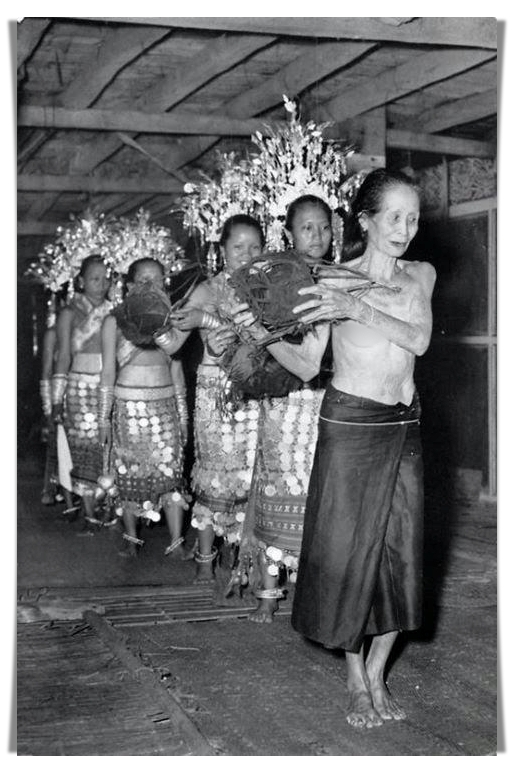

Prior to the coming of Christianity and Islam, the Iban people had a sophisticated system of animistic beliefs. The world was believed to be filled with spirits—some friendly, others unpredictable—who lived in jungles, rivers, animals, and dreams. The desire to live in harmony with these invisible forces influenced many aspects of life, from farming and hunting to warfare and family decisions.

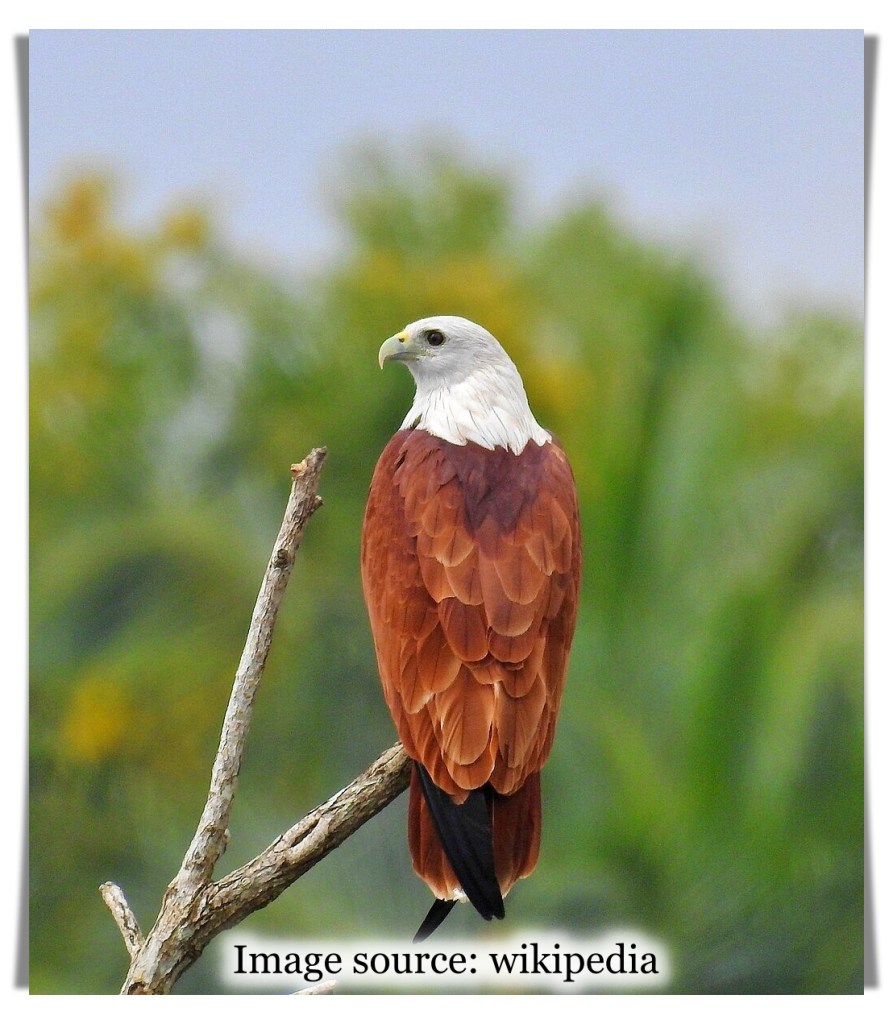

Augury, or “beburong” in Iban, was one of the most intricate systems in this belief. It is a sacred form of divination that uses the movements and sounds of certain birds known as burung mali (omen birds) to seek direction. The practice was said to have been taught to humans by Sengalang Burong, the Iban God of War and divine messenger. He taught that the gods do not speak directly but send their messages through the natural world.

Every omen bird has a specific meaning. The interpretation of their cries, flight paths, and actions guides important decisions, such as whether to start planting paddy, go on a journey, or go to war. The tuai burong, an augur who can read and understand the language of birds, is responsible for figuring out what these signs mean. This cultural duty used to be a big part of Iban life because it was a way for people to connect spiritually and keep their conduct in line with God’s will.

Oral history states that Sengalang Burong and his wife, Endu Sudan Berinjan Bungkong, had seven daughters and one son. Each daughter married a nobleman who became one of the seven omen birds: Ketupong (Rufous Piculet), Beragai (Scarlet-Rumped Trogon), Bejampong (Crested Jay), Pangkas (Maroon Woodpecker), Embuas (Banded Kingfisher), Kelabu Papau (Diard’s Trogon), and Burung Malam, which literally means “night bird” but is a cricket. The eighth omen bird, Nendak (White-Rumped Shama), is Sengalang Burong’s faithful messenger. All of these are real, common bird species that live in the Borneo rainforest.

Sengalang Burong passed down the knowledge of augury to his grandson, Sera Gunting. Sera Gunting is the son of Sengalang Burong’s eldest daughter, Endu Dara Tinchin Temaga, and her second husband, a man named Menggin. Sera Gunting also learned the omens of war when he joined a ngayau (headhunting) expedition with his seven uncles—the noblemen who married Sengalang Burong’s daughters. He later passed his knowledge to his descendants. Linggir Mali Lebu, Orang Kaya Pemancha Dana Bayang, and Unggang Lebor Menoa were among the subsequent generations of Iban war leaders who observed and practiced the war omens he had learned.

Sengalang Burong also taught Sera Gunting about the different stages of Gawai Burong, the festival that war leaders had to hold to invite him and his followers to attend. That is a story and post for another time.

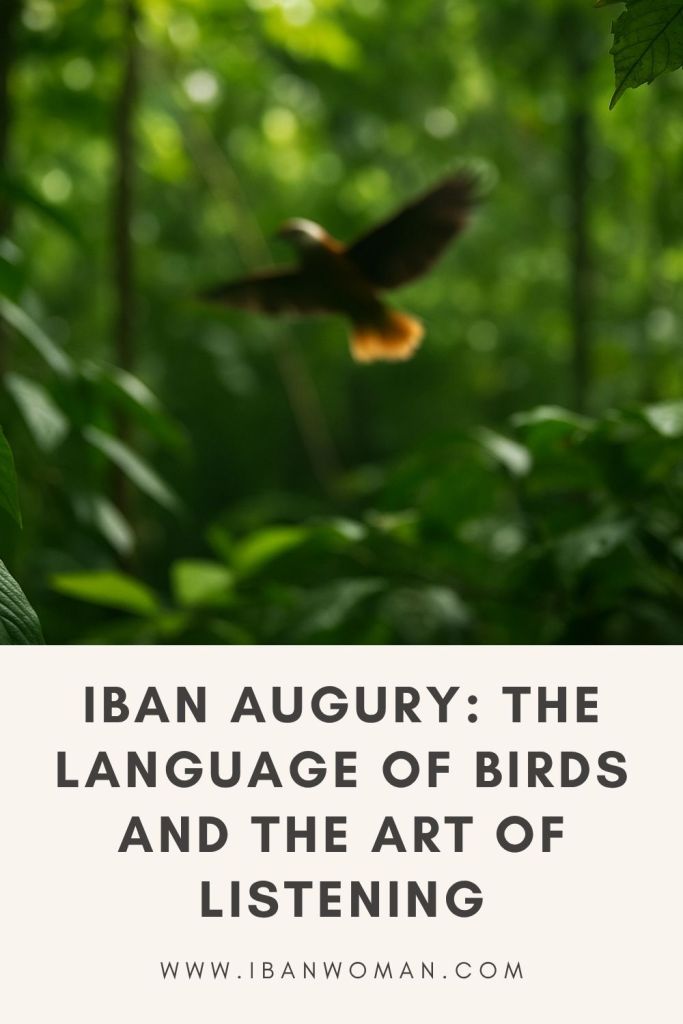

All the omen birds mentioned above can still be found in Borneo’s rainforests. I have never seen them in the wild or heard their calls in person, but last month, when I visited the Borneo Cultures Museum, I had the opportunity to hear recorded calls from Beragai and Embuas. I could hear the sound of wind, insects, and other birds in the distance along with their calls in the recordings. It was difficult to tell which bird made which sound. It reminded me that to practice augury, you needed to believe and have an attentive ear to pay close attention to the different bird calls.

Those recordings brought back a memory from my childhood. When I was nine years old, my parents decided to adopt the baby son of a relative. They had everything ready: a small bassinet, baby clothes, and the trip to the longhouse where the child was staying. They had to walk through the jungle for three hours to reach the place.

Along the way, they encountered an omen bird. I don’t know which one it was, but a tuai burong was consulted to explain the sign. He advised my parents not to continue. He said that if they went through with the adoption, the boy would grow up to “overrule” me and my siblings, which means he would prosper more than us and that we might fall into misfortune. My parents took the advice and chose not to go through with it. The baby stayed with his other relatives, and that was the end of it.

Looking back, I understand that moment not as superstition but as a reflection of how much faith my parents had in the way things were meant to be. They thought that signs meant something and that the natural world could warn or guide us through nature’s language. It was a way of life built on attention, not control. However, it didn’t stop me from wondering, what if the boy experienced a difficult childhood filled with poverty and hardship and was denied the chance to live a better life due to the bird’s signs?

Today I realized how rarely I listen. The world around me is full of noise—machines, traffic, and incessant messages devoid of meaning. Even in silence, my mind is busy with thoughts, endless scrolling, or work. Listening feels like a lost art. I no longer know how to hear what my forefathers intuitively understood: that signs came quietly, without noise or spectacle.

I’m not sure if anyone still practices augury today. Perhaps a few elders still possess fragments of that knowledge. Even if it is no longer practiced, I hope that Ibans, particularly the younger generation, understand its origins and significance. Beburong was once central to how our people made decisions and understood their relationship with nature. It influenced how they approached the world—with respect, patience, and a willingness to listen. Perhaps I’ll never see those birds in the wild or hear their true calls across the forest. But I’d like to believe they’re still there, their voices blending with the wind, delivering guidance that once guided entire communities.

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.