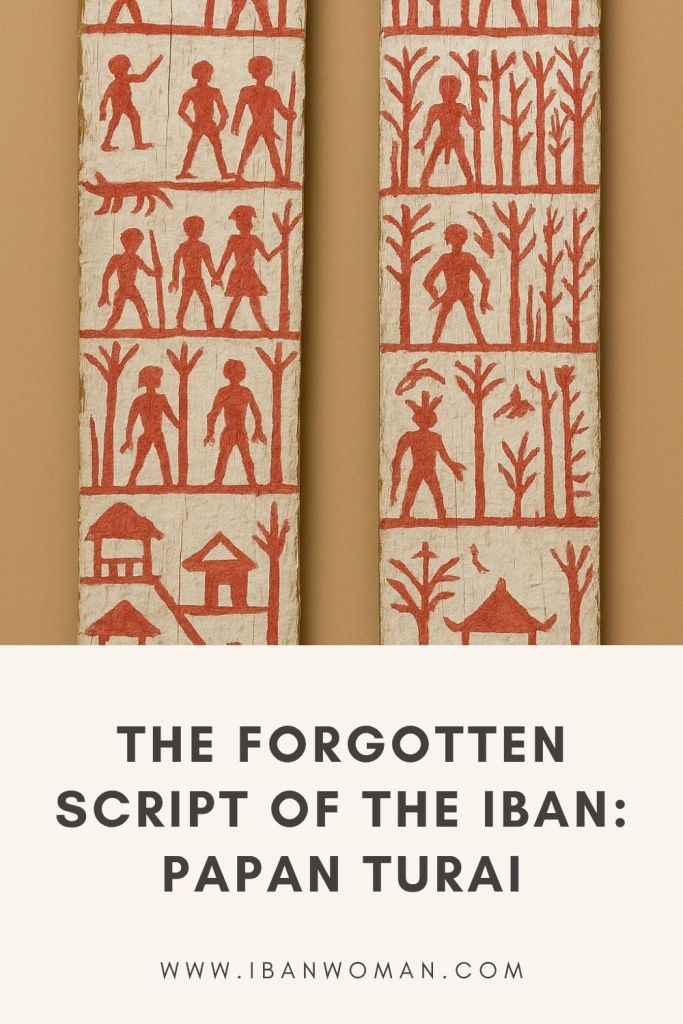

The majority of us are familiar with Egyptian hieroglyphics. However, not many people are aware that the Iban used to have their own type of pictorial writing. My ancestors’ written language, known as “turai,” is carved onto wooden boards called “papan turai.” During major festivals like Gawai Batu and Gawai Antu, lemambang (ritual bards) used these boards to recall and recite the pengap (folk epics), timang (invocations), and many other types of Iban poetry (leka main asal).

The papan turai is more than just a ceremonial piece. It serves as a link between oral and written tradition. Some of these carved symbols date back about four centuries. They preserve fragments of genealogy (tusut), the Iban’s migration history from the Kapuas region of Kalimantan to Sarawak, and even tales of tribal conflicts and legendary Iban leaders.

Researchers from the Sarawak Museum and UNIMAS have been examining these boards to find out what they symbolize. What is remarkable is that lemambang from various areas can comprehend each other’s papan turai. This demonstrates that there was once a common symbolic language among people in different communities.

This discovery goes against the previous belief that the Iban were completely “pre-literate” before Western influence arrived. The papan turai shows that our forefathers had their own way of keeping records of what they knew, which was based on ritual, cosmology, and collective memory. It reminds us that being able to read and write doesn’t just imply knowing the alphabet and how to write on paper.

In 1947, an Iban scholar named Dunging anak Gunggu expanded upon this tradition. He developed a whole writing system based on turai. However, few people know about this writing system, even among Sarawakians.

When I stood in front of the papan turai at the Borneo Cultures Museum, I felt a sense of recognition. They reminded me of the pua kumbu patterns that Iban women wove to tell stories about spirits, dreams, and journeys. Both have the same goal: to record, remember, and preserve meaning alive beyond the present.

It made me realize that each culture had its unique way of retaining memories. Some people carve it into stone, some into wood, others into sound, and yet others into cloth. For the Iban, it may have been all of these things at once. The lemambang sang what the papan turai contained, and the pua weavers wove tales and ancestral history into the thread. These were our books before books.

As I stood there, I thought about how easily such histories fade away. It’s not because they aren’t relevant, but because they aren’t documented in the systems that the world relies on. The papan turai lived on through continuity of ritual and faith. Its knowledge lived on through the lemambang, in various ceremonies and festivals, and in the community gathered around the ruai during Gawai. When modern eyes look at the papan turai, they may see only strange markings. But these are not just symbols. They hold our heritage. They are reminders that our people were already keeping records of their lives in their own way long before British colonials came with pen and paper. However, I am not sure how long we can keep them alive, as the lemambang is becoming a dying breed of heritage guardians of the Iban.

I felt pride and loss as I left the museum that day. Pride, since the papan turai shows that Iban civilization was more complicated and deep than most people realize. Loss, because so few of us can interpret those symbols today.

Maybe this is why I write and draw. I want to continue that old rhythm in a new form. My writings and drawings are like my own papan turai, illustrating the lines that connect the past and the present. I strive to document things that could otherwise disappear, including stories from my indigenous perspective, feelings, and fragments of my identity.

To me, the papan turai is more than an artifact. It is a mirror that reflects an ancient hunger to make meaning clear and to preserve memories alive before they disappear. And maybe that instinct to leave a mark and to tell a story is something that never truly goes away. It exists in our language, our art, and our digital words. It’s the same urge that led a lemambang to carve symbols into wood hundreds of years ago, hoping that someone would remember it someday.

Sources: Religious Rites and Customs of the Iban or Dyaks of Sarawak by Leo Nyuak and Edm. Dunn (1906), UNIMAS Gazette.

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.