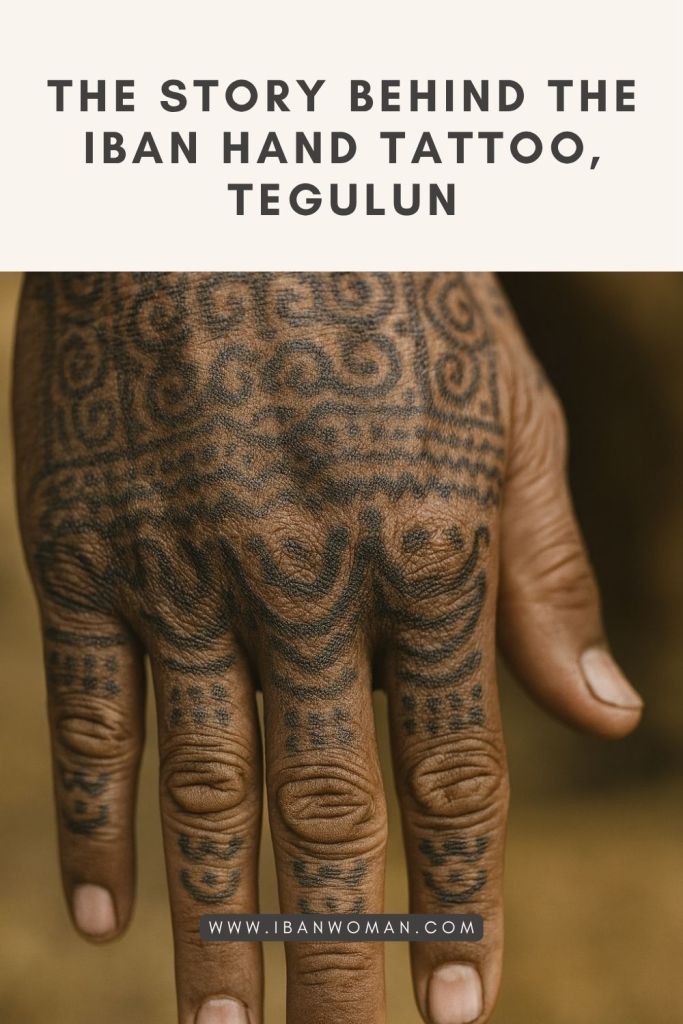

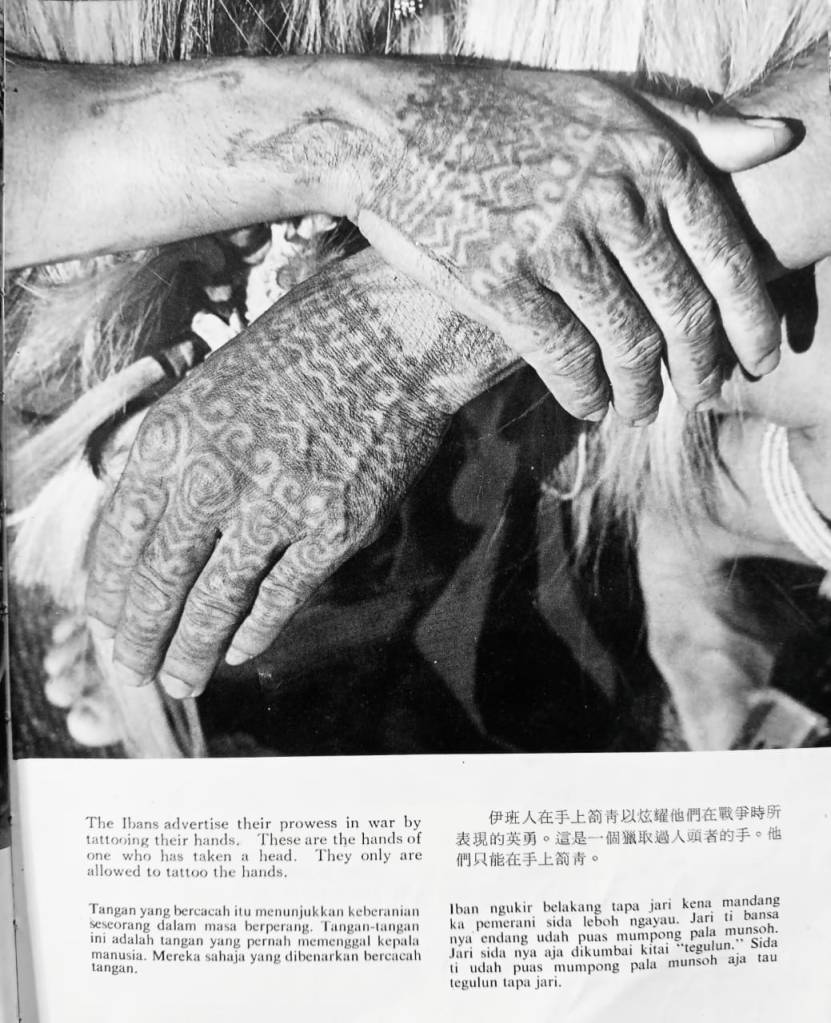

Have you ever heard of the Iban hand tattoo called tegulun? It’s one of the most striking forms of body art in our culture, yet not many people know what it really means. I found an old photo taken in 1962 from Life in a Longhouse by Hedda Morrison. It shows the hands of an Iban man with very detailed tattoos that go all the way down to his fingers. The pattern is tegulun.

In the Iban language, tattoos are called pantang or kalingai. Every tattoo on the body used to mean something. Tattoos weren’t fashion statements but they were living records of a person’s journey, courage, and place in the community. Each motif, like bungai terung (eggplant flower), ketam (crab), or kala (scorpion), meant something. For men, tattoos often showed that they participated in headhunting expeditions, or gone through rites of passage. For women, only the most skilled pua kumbu weavers were allowed to bear them.

Among women, the right to be tattooed was not given lightly. A woman known as “Indu Tau Nakar, Indu Tau Gaar”, was a master weaver who earned her tegulun through artistic and spiritual labor. With her hands, she made sacred pua kumbu cloths used in rituals such as receiving enemy heads. The tattoo on her fingers didn’t symbolize violence; it reflected her connection to the spirit world through weaving. These women were highly respected, for they were believed to hold the gift to translate dreams and visions into woven form.

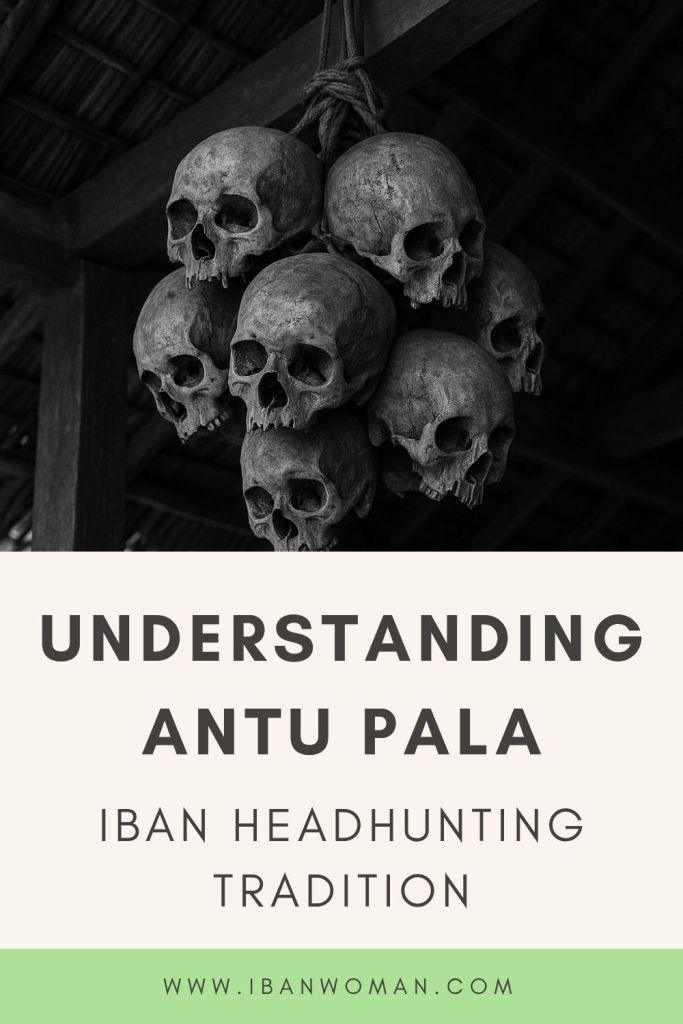

The meaning of tegulun was very different for men. Those who carried it were known as kala bedengah—warriors who had taken part in ngayau, or headhunting expeditions. Someone who had tegulun on his hands was a man who had proven himself in battle. The tattoo was a visible sign of his courage and strength of spirit. It was said that every line or curve on the fingers stood for a head of an enemy that had been killed in the war.

Looking at those tattooed fingers in old photographs, one can almost feel their importance in the past. The men who bore them were not only fighters but also protectors of their culture and their way of life. They lived by a complex set of moral codes that were based on omens, dreams, and rituals. Taking a head was never an act of impulse; it was part of a ceremony tied to the safety, fertility, and prosperity of the longhouse.

One of the most well-known Iban warriors who carried tegulun was Temenggong Koh (1870–1956), a tuai serang (war leader) from Kapit, Sarawak. His fingers were covered in tegulun, each one telling a story of victory and survival. Temenggong Koh once gave his nyabur, the sword he used during ngayau, to Malcolm MacDonald, a British diplomat. The blade still bore traces of dried blood and is now displayed at the Durham University Oriental Museum in the UK.

It’s difficult to imagine that such traditions existed within living memory. Today, there are no Iban men who bear tegulun. The British made headhunting illegal after World War II. The last “licensed” expeditions took place during the Malayan Emergency and Communist Insurgency, when Iban trackers were recruited to assist the British. After that time, the custom of taking heads and the tattoos that went with it completely died out.

The tegulun is more than a reminder of war. It refers to a time when everything, from fighting to making art, was connected to the spiritual order of the world. Tattoos linked the body to the world that can’t be seen. They reflected not only bravery but also a sense of belonging. A man or woman who bore them carried the stories of their people and passed them down through the generations.

Those meanings are at risk of being lost today. Most young Ibans have only seen people with tegulun in books or museum photos. But it’s important to understand them. These tattoos show us how our ancestors thought about life, death, and the sacred balance between the two. They remind us that strength can show itself in many ways, like when you swing a nyabur (sword) or sometimes in the patient rhythm of weaving a pua kumbu.

To learn about tegulun, you have to look beyond the surface of the skin. Though the ink has faded and the rituals have ended, the meanings remain alive in memory. They are echoes from another time, reminding us that every mark and line once carried a story worth telling and remembering.

Image source: Life in a Longhouse by Hedda Morrison

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.