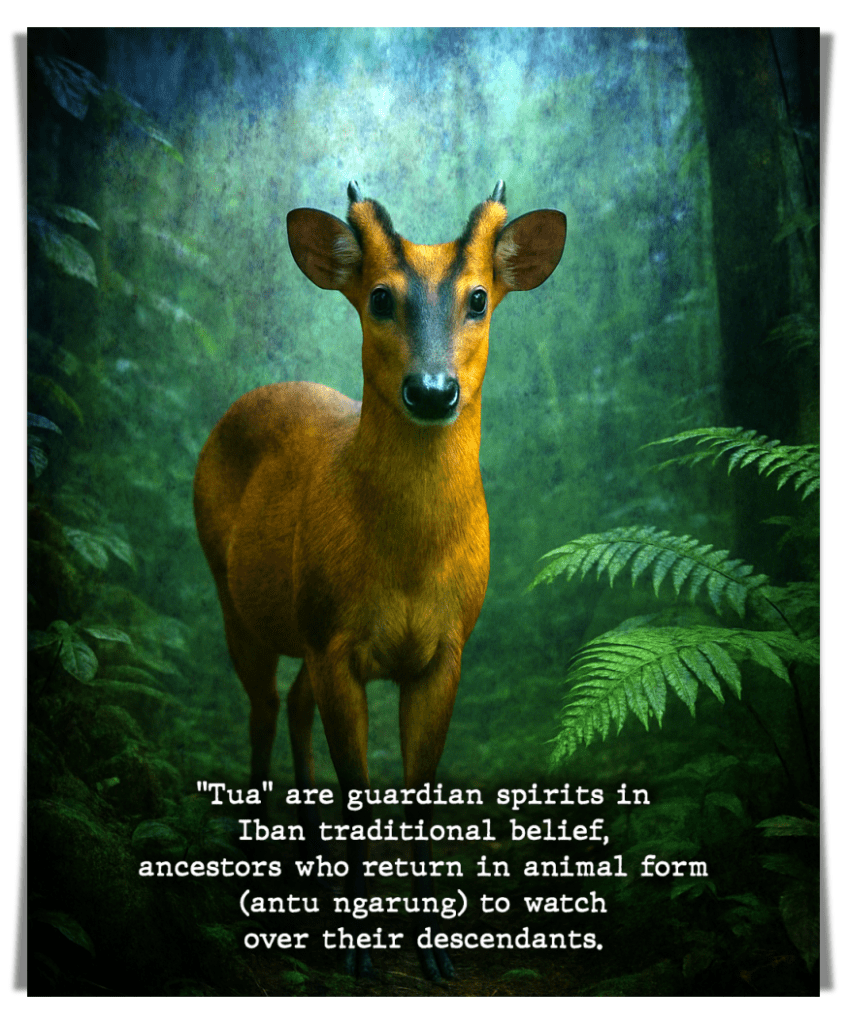

In Iban belief, the souls of those who die go to Sebayan, the afterworld. Some remain there permanently, but certain individuals are believed to return. These are people who lived with exceptional courage or accomplishment during their lifetime. When these ancestors come back, they do not appear as humans. They come ngarung, meaning concealed, taking the form of animals. These returning spirits are called tua, or guardian spirits.

In the Saribas region, guardian spirits are often seen as snakes such as cobras or pythons. They move quietly, stay in the shadows, and leave without drawing attention. When I picture antu ngarung, I always imagine a cobra coiled in the dark corner of a house or at the edge of the forest. It stays still for a long time and slips away the moment it decides to leave. To many people, it would be just an ordinary animal. To us, it can be an ancestor paying a visit.

A guardian spirit usually belongs to an entire lineage. Because of that connection, the family must never harm or eat the animal that represents their guardian. This is a form of respect. The belief is straightforward: the guardian protects the family, and the family must protect the guardian’s form on earth.

In my family, our guardian is the kijang, the Bornean yellow muntjac. When I was four or five, my late grandparents reminded us repeatedly never to harm, kill, or eat kijang. They did not offer long explanations, but the message was clear. Someone in our line was once a brave person, and that ancestor is believed to return as the kijang to watch over us.

That instruction frightened me growing up. I was afraid I might break the rule by accident. I used to remind myself to always ask what kind of meat was being served when we visited people. At that age, it felt like a tremendous responsibility. Over time, the fear changed. I started to feel that my life was connected to something older and larger than myself. I also realised that this experience was not common among many non-Iban communities, which made me value my heritage even more.

The belief in the kijang has shaped the way I understand myself. It gives me a sense of courage. I am still afraid of many things, but this belief keeps me steady. It reminds me that my ancestors lived through hardship, violence, and uncertainty. My problems today are nothing like what they endured. I often tell myself to live in a way that does not dishonor the people who came before me. I exist today because they survived so much. That thought helps me face difficult moments.

When I imagine the kijang watching me now, I think it sees a woman who lives differently from the Iban women of earlier generations. My lifestyle and interests are not the same. Yet I believe it recognises my effort to understand my roots. It may also encourage me to continue forging my own path even when no one else in my family is doing this kind of work. Many women in my family excel in traditional crafts like beadwork and weaving, but none of them are writers. I have to accept that I may be the first woman in my family to preserve our heritage through writing. Someone younger in the future may look at my work the way I once looked at my namesake, the master weaver. Remembering this keeps me going, even when the work feels lonely.

This leads to something important.

We risk losing our identity when we do not learn about our heritage. The loss does not happen suddenly. It happens slowly. We begin identifying more with other cultures. We forget the meaning behind our names, our customs, and our stories. When we fail to protect what we inherit, we leave an empty space that can be filled by influences that do not reflect who we are. This is happening in many communities around the world, and the Iban are no exception.

Iban identity will not endure by chance. It survives because someone chooses to learn, write, document, and share it. It stays alive when people believe their heritage is worth protecting. It continues when people care enough to ask questions and remember the stories their elders passed down.

Our ancestors returned as antu ngarung for a reason. We owe it to them to honor the heritage they entrusted to us.

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.