I used to think that rituals like beserara’ bungai were just old traditions that had no place in today’s world. Growing up, I believed they belonged to the past. I thought the Iban needed to leave them behind to move forward. Whenever elders talked about these beliefs, I felt restless. My world revolved around progress, education, and the principles of organized religion. I didn’t see the value of rituals, and I never took the time to understand what they really meant.

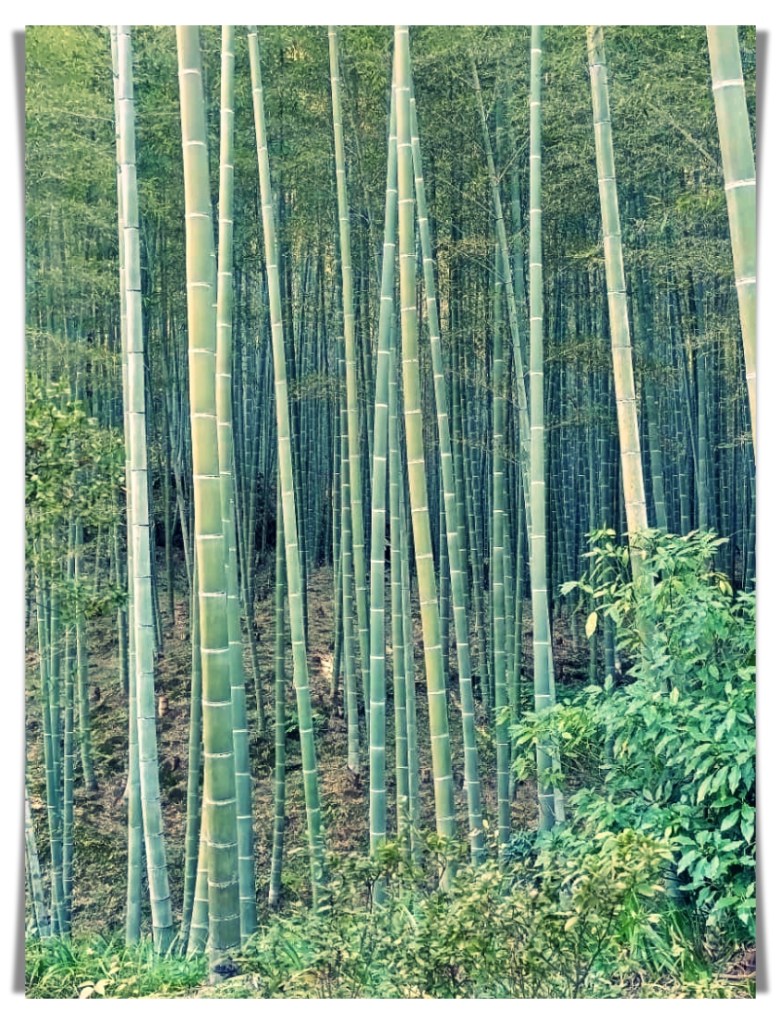

That mindset began to shift—slowly at first, then more clearly—as I read more about the Iban worldview. It wasn’t emotion or nostalgia that changed me, but understanding. I began to see that the Iban learned about life by watching the natural world. They noticed patterns in nature and connected them to how we live. For example, they saw how bamboo and banana plants grow in clusters. Each shoot is part of a single root system underground. If one shoot is unhealthy, it affects the others. When one dies, the root still supports new life. Death was not an ending but part of the cycle. This wasn’t superstition, but wisdom based on careful observation.

The bungai, the “plant-image” that represents each Iban person in the cosmic realm of Menjaya (the god of healing), began to make sense to me. I understood how it symbolized family and community. Each person is like a shoot, but we all come from the same root. When someone passes, the rest carry on, still connected. New life can grow from the same source. It’s a way of seeing life that is deeply connected and respectful of nature. The ancestors weren’t imagining things—they were describing the interconnected world they knew.

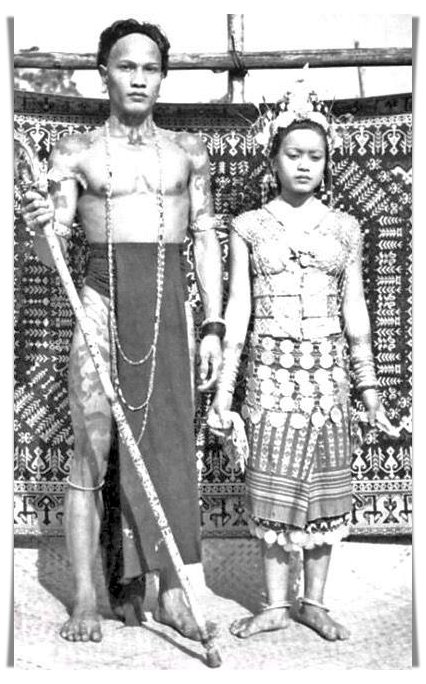

As I learned more, I started to feel a quiet pride in where I come from. I discovered that my ancestors included warriors and raja berani, people whose stories are still told in my family. I began to understand that even though I live far from my homeland, I am still part of that root system. This connection also extends to my children. They may not know all the customs or speak the language well, but the roots are still there. They are part of something that has been passed down through generations.

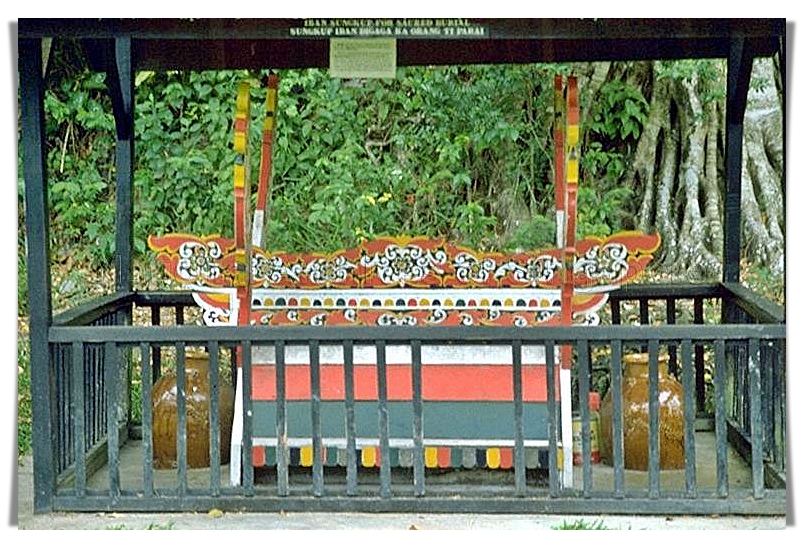

When I learned about beserara’ bungai, the ritual that separates the living from the dead, I felt something shift in me. This ritual is about care—not forgetting what we have lost. It helps both the living and the dead let go so they don’t hold each other back. The living need to keep moving forward, and the dead need peace on their journey to Sebayan. It’s a ritual of compassion that affirms the connection with the dead even as they journey on to the otherworld.

This understanding arrived at a time when I was wrestling with my own spiritual ties. I had been part of the same church community for many years. It shaped how I saw God, faith, and morality. But as I grew older, those teachings started to feel burdensome. I found myself questioning doctrines that encouraged separation from people who did not meet certain standards of spirituality. I began noticing the tension between fear-based expectations and the compassion-centered teachings of Jesus in the Gospels. As I continued to question, the burden of belonging to a system that no longer aligned with my conscience intensified.

Learning about beserara’ bungai gave me words for what I was feeling. I realized I was trying to protect my spirit. I wasn’t leaving faith behind—I was returning to what felt true. Jesus became the real rootstock. I wanted a faith grounded in his teachings: kindness, justice, presence, love, and compassion—not fear or guilt. I needed space to grow without feeling judged by a community that often equated questions with spiritual instability.

In a way, I’m experiencing my own kind of separation from the church rootstock. It is not a rejection of my past or of the people who have been a huge part of my life for the past two decades. It is a necessary separation so I can continue growing without feeling suffocated by expectations that no longer fit the life I am trying to build. I’m holding onto what still nourishes me and letting go of what drains me. The Iban worldview helped me understand that letting go can be a way of protecting both myself and the things I want to keep alive.

The more I reflect on it, the more I hope my children learn something different from what I learned in my early years of faith. I hope they are not afraid to ask questions. I hope they do not feel inferior in front of people who sound knowledgeable but speak without warmth. I want them to grow into a faith that welcomes curiosity, thoughtfulness, and conscience. I want them to recognize that their connection to God is direct, personal, and rooted in compassion—not fear. I want them to inherit a sense of strength that comes from understanding where they come from, both culturally and spiritually.

As I learn more about rituals like beserara’ bungai, I’ve come to understand that my ancestors didn’t divide life into “spiritual” and “ordinary.” Everything was connected. Life, death, nature, community, and spirit were all part of one whole. That way of seeing the world teaches me to live with care and humility. It shows me that letting go can be a loving act, and returning to our roots can take courage.

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.