A quick disclaimer before I begin. Some people may find this topic upsetting because headhunting led to conflict between different ethnic groups. I don’t intend to glorify the practices of my ancestors; I just want to share what I know, especially since many people, even younger Ibans, don’t fully understand the reasons behind it. Taking a life is wrong by today’s standards, and from a modern perspective I do not support it. But we can’t change history, and judging the past by our present lens doesn’t help us understand it. What we can do is listen and learn.

The Iban had their own reasons and beliefs for taking heads. One of the most significant was to end the mourning period, a practice called ngetas ulit. When someone in the community died, the longhouse would mourn for a period of time. During this time, certain rules and taboos were followed. A ritual that demanded a fresh head was performed to end the mourning period. The family of the deceased would consult the longhouse community, and the men would plan a ngayau (head-hunting expedition) together. After getting a head, a series of complex rituals signaled the end of grief. Killing to end mourning may sound strange today, but for the Iban it was part of a cultural process called nyilih pemati, a symbolic offering for the dead.

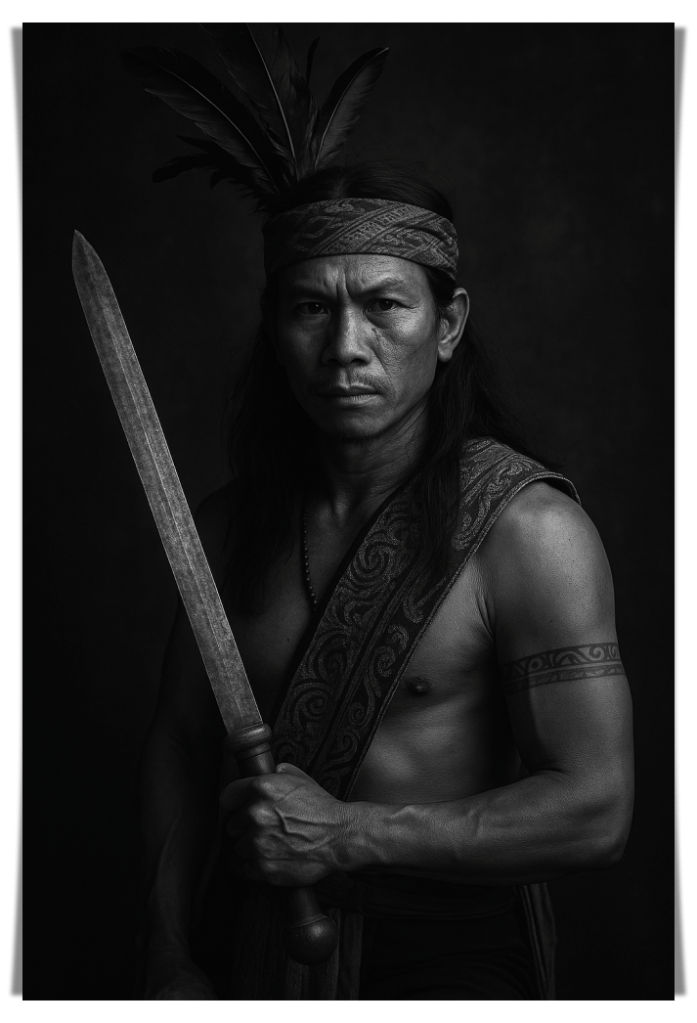

Another reason was the belief that antu pala (enemy skulls) had spiritual power. The Iban in the old days believed that these skulls would bring blessings if they were taken care of. Antu pala also played an important part in the Gawai Burung (the Bird Festival), which was one of the most important Iban ceremonies. As part of this complicated ceremony, the lemambang (bard) would use the skulls in his pengap (chants) to invoke the god of war, Sengalang Burong. This festival has probably disappeared because most Ibans are now Christian or Muslim, but it still holds a place in oral tradition.

There were other uses for skulls as well. They were used in healing rituals, ceremonies to call for rain during times of drought, and as guardians to protect the longhouse or farms from enemies and wild animals. In this regard, the skull became a spiritual servant for the person who kept it. They also carried social meaning. If a man didn’t take a head, he was likely called a coward or kulup (uncircumcised), and these men were not seen as good husbands. Iban society valued courage and bravery very highly.

Some have asked why heads were taken instead of other body parts. The answer lies in old beliefs. Our ancestors believed that the head was the center of a person’s life force. The head could be clearly identified, unlike the hands or feet. In the past, families knew exactly whose head was kept, even after years of blackening from smoke. Today, those identities are no longer shared openly. Imagine getting married to someone from another tribe and then walking into a longhouse and saying, “Honey, that skull belonged to your ancestor.” We have learned that silence is a way to protect the living while still honoring the past.

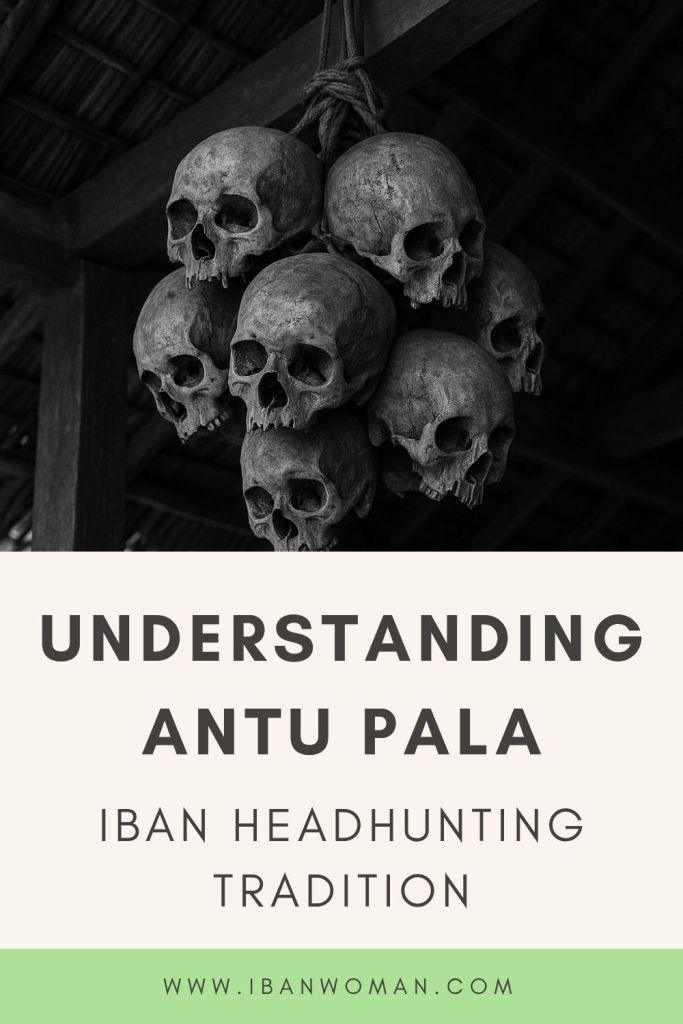

So, do antu pala still exist? Yes. Some Iban families keep them, like mine. They can be kept in the sadau (the top floor of the longhouse) or hung in groups called tampun on the roof. We don’t see them as trophies but as things that deserve respect. If you don’t take care of them, they can bring bad luck, so you must abide by strict rituals to keep them safe.

This picture shows a tampun that belonged to my ancestor, Unggang Lebur Menua, an Iban warrior from the late 18th century. It has 34 antu pala that are more than 200 years old, and is now kept by relatives at Rh. Panjang Matop, Paku, Betong. It serves as a reminder of a different time, when survival, belief, and identity were connected in ways that may be difficult for us to understand now.

I hope this helped you learn more about a part of Iban history that continues to live in our collective memory.

Image source: Youtube

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.