TL;DR:

A simplified overview of traditional Iban animistic beliefs, including the Supreme God (Petara), nature spirits, ancestral souls, and mystical beings like Kumang and Keling. These oral stories, once passed down generation to generation, are now slowly being archived here from my Threads posts for easier access and deeper reflection.

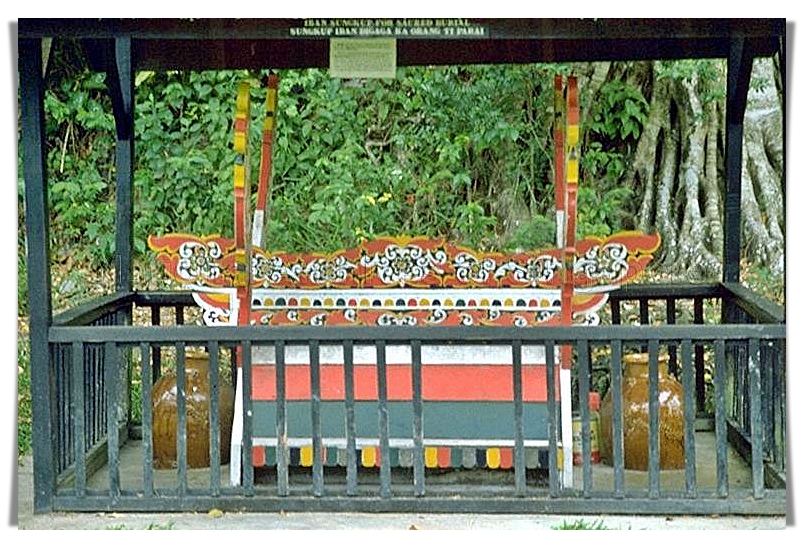

Prior to the arrival of Christianity and Islam, the Iban people practiced a form of animism. It’s a complex belief system where spirits existed in rivers, jungles, animals, dreams, and even illnesses. Though most Ibans today identify as Christians, many still observe traditional customs during weddings, festivals, and ancestral rites. It’s worth noting that the Iban never had a written system to record these beliefs. Every story and ritual was passed down orally from one generation to the next. Because of this, different river regions or divisions often have slightly different versions of the same story, each molded by the voices and landscapes that keep them alive.

Here is a short, simple summary of this complex cosmology that you can use as a reference. I’ve been actively posting about Iban culture, legends, and folklore on Threads, but now I’m slowly fleshing them out and archiving them here for my readers.

Note: I’ll touch more about the Sengalang Burong’s family when I write about Iban omens and augury.

Core Beliefs

Iban animism is based on the idea that there are many spiritual beings that are part of everyday life and the afterlife. These include:

- Supreme God, called Petara / Tuhan or Raja Entala

- Deities and spirits, called Bunsu Petara – each with their own roles i.e Sengalang Burong

- Spirits of ancestors, called Petara Aki Ini – often called upon during rites like Gawai Antu i.e roh nenek moyang

- Spirits of nature, found in animals, plants, rivers, and forests and also include Bunsu Antu i.e jin, iblis

- Mystical beings from the sky realm called Panggau Libau and Gelong i.e Kumang, Keling

Dreams were (and still are) taken seriously, often seen as spiritual messages. If a deity (i.e Sengalang Burong) or mystical being (i.e Kumang) appears in a dream, it’s treated as guidance that must be followed.

Categories of Gods and Spirits

1) Petara / Tuhan (Supreme God)

- Also known as Raja Entala

- Creator of all living things

2) Seven Main Deities / Bunsu Petara (Who live in the realm of Tangsang Kenyalang)

These seven deities are the children of Raja Jembu and Endu Endat Baku Kansat. Raja Jembu is the son of Raja Durong and Endu Kumang Cheremin Bintang. There is more to this lineage, but for simplicity, let’s just focus on Raja Jembu’s family. These seven deities or Bunsu Petara, are often invoked in Iban poetry, like pengap and timang.

- Sengalang Burong – God of war (Sengalang Burong’s wife is Endu Sudan Beringan Bungkong. They have eight children including a daughter, Endu Dara Tinchin Temaga)

- Biku Bunsu Petara – God of resources

- Sempulang Gana – God of agriculture

- Selempandai – God of creation and procreation

- Menjaya Manang – God of healing

- Anda Mara – God of wealth

- Ini Andan – Female spirit doctor and goddess of justice

3) Mystical Beings (Who live in the land above the sky, Panggau Libau and Gelong)

- Kumang, Keling Gerasi Nading, Kelinah Indai Abang (Keling’s sister), Lulong, Laja, Pungga, Selinggar Matahari, Sempurai Bungai Nuing, Tutong (Kumang’s brother) – Divine beings who help humans succeed in life, especially warriors and brave people. Kumang and Keling appeared more in dreams compare to the rest.

4) Spirits of Nature

- Bunsu Jelu – Animal spirits

- Antu Utai Tumboh – Plant spirits

- Bunsu Antu – Ghosts or restless spirits, some helpful, some harmful

5) Souls of Ancestors / Petara Aki Ini

- Honored during rituals like Gawai Antu

- Believed to offer blessings and protection when remembered properly

Copyright © Olivia JD 2025

All Rights Reserved.

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.