Some time ago I began writing Fragments of Obsession, brief glimpses into a private world of desire and distance. These new pieces pick up where the last ones left off, but they explore a darker area: the world of a criminologist.

I can’t sit at his desk or walk with him into the places he inhabits. All I have are fragments, imagined through the silence between us. They’re not about the crimes themselves but rather the places around them: his desk, the crime scene, and the interrogation room.

What interests me is not the evidence he gathers, but the burden that persists afterward. These pieces are how I watch from the outside and write about things I’ll never see. They belong to the same map of longing I began tracing in the first three Fragments of Obsession — part 1, part 2, part 3.

The Desk

I never stood in front of it, but I know it like I’ve touched its surface a thousand times in my mind. A desk that holds the stories that no one wants to tell, and even fewer want to hear. Its top is scratched, probably from years of people dropping folders, forgotten coffee cups, and constant shuffles of pens and clips. Sturdy but with scars like him.

On one side, there is an uneven stack of papers threatening to tumble. Case notes, autopsy reports, and transcripts of late-night interviews with men who lie easily and women who have given up on getting justice. I imagine the edges fading from being read too often, held in worn hands. Underneath them, photographs turned face down, and the victim’s eyes still burning even when hidden.

The other side is neater. A computer. A notebook with a page full of his neat, small handwriting. His pen would sometimes rest diagonally across it, with ink smudges on the margins where he applied pressure too hard. I imagine him hesitating mid-thought, his brows furrowing.

There must be a hidden gun nearby. Cold, clinical, and within his reach. The barrel pointing nowhere, a constant reminder of how violence is always a part of his life. My people never lived with guns except for the ones that were passed down to us. My grandfather’s shotgun passed to my father and now to my eldest brother. A hunting tool, not for murder. Unloaded but heavy with potential, lingering like a sinister presence at the periphery of every thought.

I can see his hand, with raised veins and long fingers, tracing the tabletop absentmindedly when fatigue creeps in. A gesture that seems almost loving, as if he were anchoring himself. He’s a man who has read too many lies in too many statements. He doesn’t stop. He keeps returning to this desk, like a man returning to his menua, the land he was born in, where his roots are waiting for him, no matter how far he has gone.

I’ll never sit across from him there. I only know it through imagination. This distance allows me to observe things that others may overlook: the silence around him, the way the desk has become an extension of his body, his determination, and his solitude.

The Crime Scene

I picture it as the opposite of his desk. No order, no familiar scratches, no steady ground. There was chaos sealed off by yellow tape. It’s a place where a life has ended and everything normal—shoes by the door, a half-empty cup on the table, a curtain in the wind—suddenly feels obscene.

The air is thick with things that can’t be cleaned. The iron tang of blood and the sour staleness of fear. A house where someone used to laugh is now silent. He goes through it methodically, but I know he notices everything. The scattered belongings. How things look wrong when they aren’t where they belong. The imprint of violence that remains like smoke after a fire.

He kneels by the details others step over. A broken clasp. Mud tracked across the tiles. Fibers snagged on a nail. His hand hovers above them, never in a hurry or careless. He bends down low to collect evidence. I imagine how his eyes narrow as he gathers pieces that the rest of us can’t see.

Somewhere close, a camera flashes, officers talk, and someone fills in a logbook. He moves like none of them are there. The scene is speaking to him. It tells him what to look for, what to doubt, and what doesn’t belong.

And maybe he thinks of the victim too. Not just as a body drawn in chalk, but as a person who went barefoot over this floor and brushed their teeth at that sink. He’s seen too many of them. Each scene digs into him like a thumbnail.

According to my people, when someone dies tragically, the place becomes restless. You don’t linger there long unless you want to carry that darkness home. He has to stay. He lets the silence seep into him and the darkness push against his skin. This is the only way to read what the dead left behind. The chaos doesn’t stay behind when he finally steps back over the tape. It follows him and becomes the real evidence he can never log.

The Interrogation Room

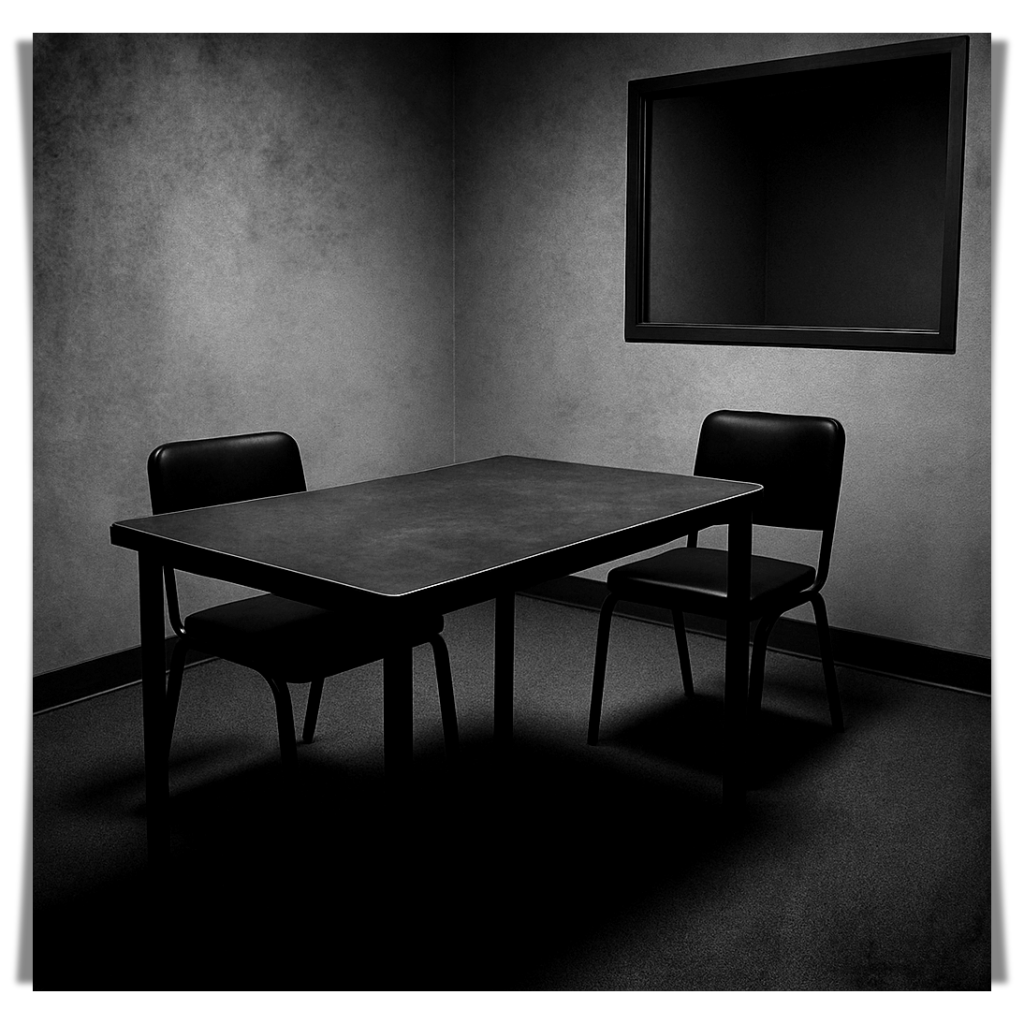

I can see it clearly, even though I’ve never been inside. The walls are bare and dull gray with faint finger prints on the paint from palms dragged in terror, boredom, or defiance. A single table in the center with uneven legs. One chair on each side but only one feels in charge.

I imagine the air stale with breath and the absence of sunlight. There are no windows to the outside world. Only a dark pane of glass on one wall. He knows they’re watching. He doesn’t care. His focus is always here. This is a space where people stall, spin, crack, or burn.

He sits across from them. Calm. Still like the river at dusk before swallowing the last light. He doesn’t raise his voice. He waits and lets them fill the silence with their own guilt. Lets them fidget, lie, and repeat themselves. Lets them feel uncomfortable about what they said.

There’s always a file in front of him. Sometimes it’s closed. Sometimes it’s open to a photo or a sentence scribbled in red. He doesn’t look at it much. He stares at them, watches how their jaw moves, how they scratch their nose, and how their eyes dart to the door when they think no one’s watching.

I wonder if he thinks of the victim while he listens. If he remembers the angle of the neck, the bruise on the cheek, and the time of death. If he keeps those pieces in his pockets like charms, reminding him of who he’s really speaking for.

In my people’s old way of life, truth wasn’t pried out in rooms like these. We invoked Ini Andan, the goddess of justice, and waited for signs. Now there are only fluorescent lights and CCTV. The ritual remains the same. Watching. Listening. Putting the soul on a scale.

He doesn’t need to catch them lying. They’ll hand it over eventually. Little by little, like decaying meat falling apart in their hands.

Note:

I’m still working through two more fragments—The Victims and The Walk. They’ll come when they’re ready, and together they’ll complete this small sequence of obsession.

Copyright © Olivia JD 2025

All Rights Reserved.

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.