Before the arrival of Christianity and Islam, the Iban people practiced a complex system of animistic belief. The world was seen as alive with spirits; some benevolent, some unpredictable, residing in rivers, jungles, animals, and dreams. The desire to stay in harmony with these unseen forces guided every aspect of farming, hunting, and war.

Scholars such as Benedict Sandin and Clifford Sather suggest that early contact with Hindu-Minangkabau traditions from Sumatra may have influenced some aspects of Iban spirituality. These influences probably came when noblemen and their followers from the Majapahit kingdom fled westward at the end of the empire to escape persecution as Muslim rule expanded. They brought with them knowledge of rituals, governance, war, and agriculture. These ideas were slowly taken in and reinterpreted through the Iban worldview.

From this convergence emerged a cosmology rich with ritual poetry, omens, and divine intermediaries. One of its most complicated systems is augury, a sacred form of divination that reads the calls and looks of certain birds as messages from the spirit world. These omen birds are still an important part of Iban ritual life, especially during farming and community events.

Sengalang Burong, the Iban God of War and messenger of the gods, is at the heart of this belief. He established the system of augury that connects the physical world with the spiritual world. Through him, communication between the two is made possible. The living interpret every sighting and call of an omen bird as a sign from God.

Sengalang Burong: The Iban God of War

In Iban belief, Sengalang Burong is the most revered of all deities. He is remembered as both the God of War and the divine messenger who connects the world of humans with the world of gods. Many ritual invocations and prayers include his name, and people often ask him for courage, protection, and clarity.

According to oral tradition, Sengalang Burong descends from Raja Jembu, a powerful deity whose family tree goes back to Raja Durong of Sumatra. It is said that Raja Durong and his followers fled their home near the end of the Majapahit era. They brought with them religious and cultural traditions that were influenced by Hindu-Minangkabau beliefs. These encompassed ritualistic practices, frameworks of social governance, agricultural knowledge, and strategies of warfare. Over time, these ideas merged with the Iban’s indigenous worldview, creating the spiritual framework that shaped their understanding of the cosmos.

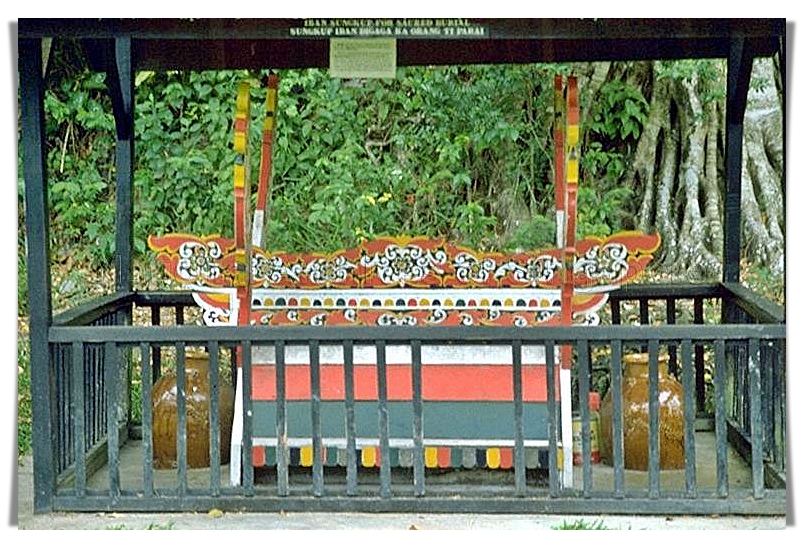

In Iban ritual liturgy, Raja Jembu is the guardian of the batu umai, which is a sacred whetstone used in Iban farming rituals. He married Endu Endat Baku Kansat, and they had six sons and one daughter together. Their children became the main pantheon of the Iban gods, Bunsu Petara.

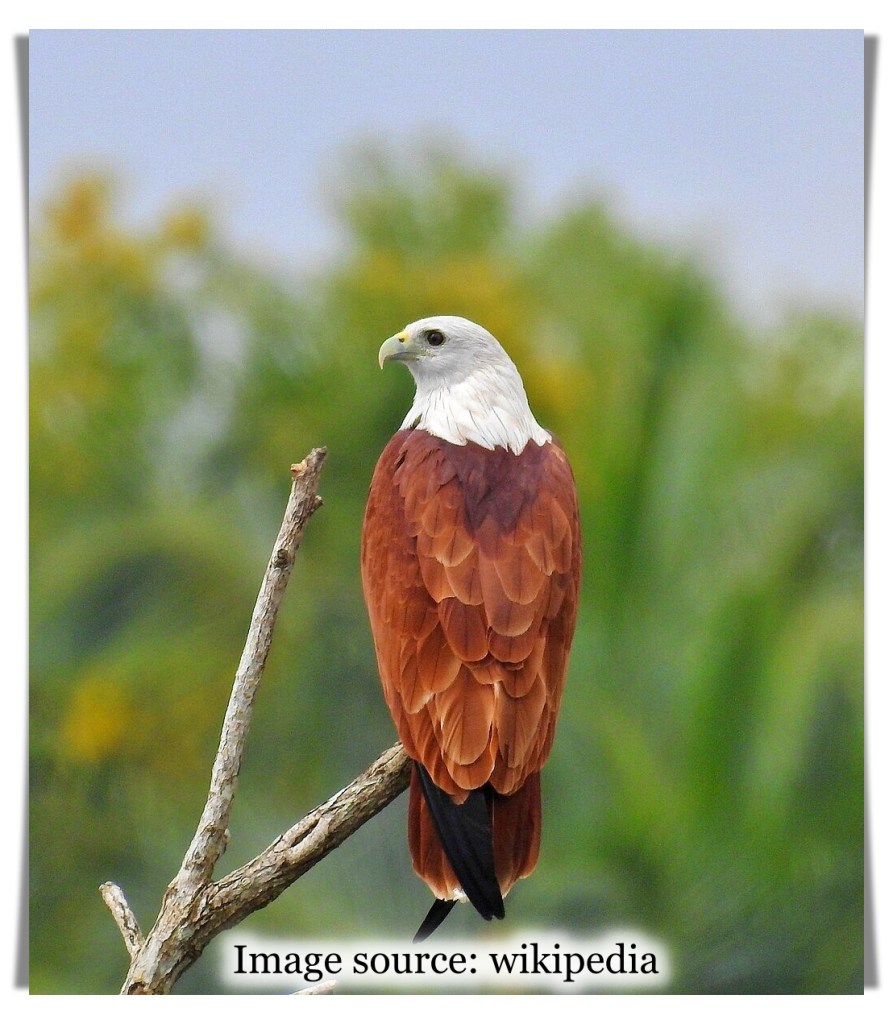

Sengalang Burong, the oldest son, rules from Tansang Kenyalang (Hornbill’s Nest), in a realm high in the sky. On earth, he transforms into a Brahminy Kite, known affectionately among the Iban as Aki Lang (Grandfather Lang). He guides humankind through omen birds that act as his messengers. Through these birds, he sends divine messages that govern decisions related to farming, war, and community affairs.

Sengalang Burong married Endu Sudan Berinjan Bungkong, and together they had seven daughters and one son. Each daughter married a nobleman who became one of the seven omen birds: Ketupong, Beragai, Bejampong, Pangkas, Embuas, Kelabu Papau, and Burung Malam. Nendak, the eighth omen bird, is Sengalang Burong’s faithful messenger.

These eight omen birds form the foundation of the Iban system of augury. Their calls, directions of flight, and behavior are interpreted during rituals to determine whether an action, such as starting a journey, planting paddy, or launching a war expedition—is blessed or forbidden. For the Iban, these signs are not superstition but sacred communication. They represent the continuing dialogue between the natural and the spiritual worlds, a system established by Sengalang Burong himself.

In future posts, I will explain more about each omen bird and its role within Iban augury.

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.