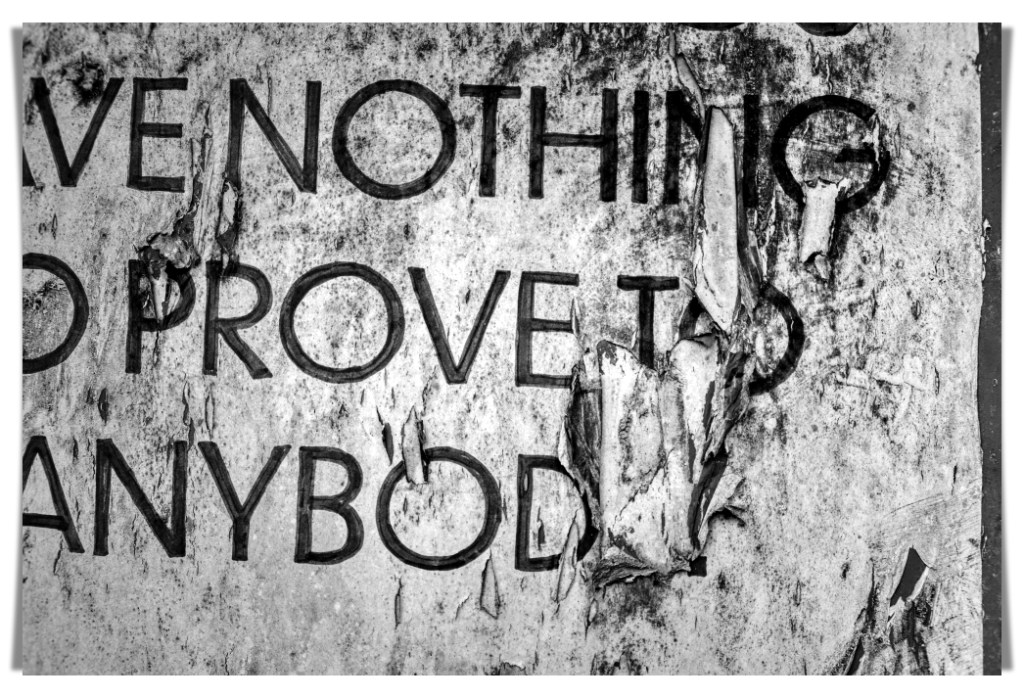

If I could get rid of one word for good, it would be “should.” That word is not rude or offensive. When someone uses it in a sentence, it doesn’t hurt or shock on impact. What gives it power is its subtlety. “Should” sounds innocent and gets overlooked easily. It often comes up in conversations disguised as common sense, advice, or concern. It sounds reasonable and hardly ever raises alarm. However, it changes how people feel about themselves without their knowledge or consent. I have noticed many people say “should” when they talk about how to live, how to feel or respond, and how to move on from something bothering them. Here are some examples:

You should be grateful.

You should know better by now.

You should forgive.

You should stay.

You should want this.

The word has power without needing to explain itself. It makes an assumption without giving any context. When spoken, it compares someone’s current situation to an implied standard. My biggest concern about “should” is how sinister it could be. Like for example, solicited advice can be helpful when it is invited. However, the harm can happen when the advice giver uses “should” to replace the important part, which is to truly listen to the person who asked for advice. When we use “should,” it enters the space before understanding has had time to grow. So you see, it comes with an assumption already in place.

I have heard “should” used most often when people aren’t sure what to do. For example, when someone is grieving or questioning their faith. Other common situations are when someone is worn out, overwhelmed, or unsure of their next step. In those times, “should” makes things less uncomfortable and easier to understand. “Should” gives direction when being patient and thinking things through might be a better option.

The word “should” does something subtle over time. It trains people to monitor themselves all the time and judge their thoughts and feelings against an unseen standard. They start to compare how they feel to what they think they should feel. They also start to compare their needs against what they believe is expected of them.

I’ve seen this happen in religious settings, where “should” is used to make people obey and not question things. I’ve seen it in conversations regarding productivity, where rest is treated as something to be earned and not a necessity. I’ve seen it used abundantly in discussions about relationships that often encouraged someone to be patient and endure instead of drawing firm boundaries. The word “should” adapts easily, and it is often used to control a narrative so it fits the controller.

One reason “should” is hard to challenge is that it often comes with good intentions. The person using it might think they are helping and being sincere. But sincerity and the impact of the word are two different things. They aren’t mutually exclusive. The impact of the word is dependent upon what it forces the listener to disregard, no matter how sincere it is being delivered. When “should” comes into a sentence, the present moment loses its value. What is felt, known, or experienced becomes temporary, like something that needs to be fixed and gotten over with.

I don’t want to replace “should” with another option. I know that certainty is still limited and that expectations still exist even without the word. In life, there will always be choices, obligations, and consequences. To get rid of “should,” we would need a different way of getting our messages across. And that would include empathy, perspectives, thorough explanation, and room for nuance. Without “should,” we would have to say what we actually mean. And we would have to talk about what we really think instead of what we think is supposed to be.

I have learned that that word, “should,” directly contributed to many difficult periods in my life. It was said so many times that I didn’t see how insidious the harm it caused. It drove me to doubt my own timing, my own limits, and also my own instincts. Banning “should” might not make things easier but it could give honesty more room to breathe. Without “should,” it would remove one of the most efficient ways to quietly erase oneself. And of course, without “should,” other ways of relating would have to take its place.

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.