“The Orang Kaya Pemancha Dana Bayang of Saribas is now with me…the dreaded and the brave, as he is termed by the natives. He is small, plain-looking and old, with his left arm disabled, and his body scarred with spear wounds. I do not dislike the look of him, and of all chiefs’ of that river I believe he is the most honest and steers his course straight enough.”

— James Brooke, The White Rajah’s Diary, 1843

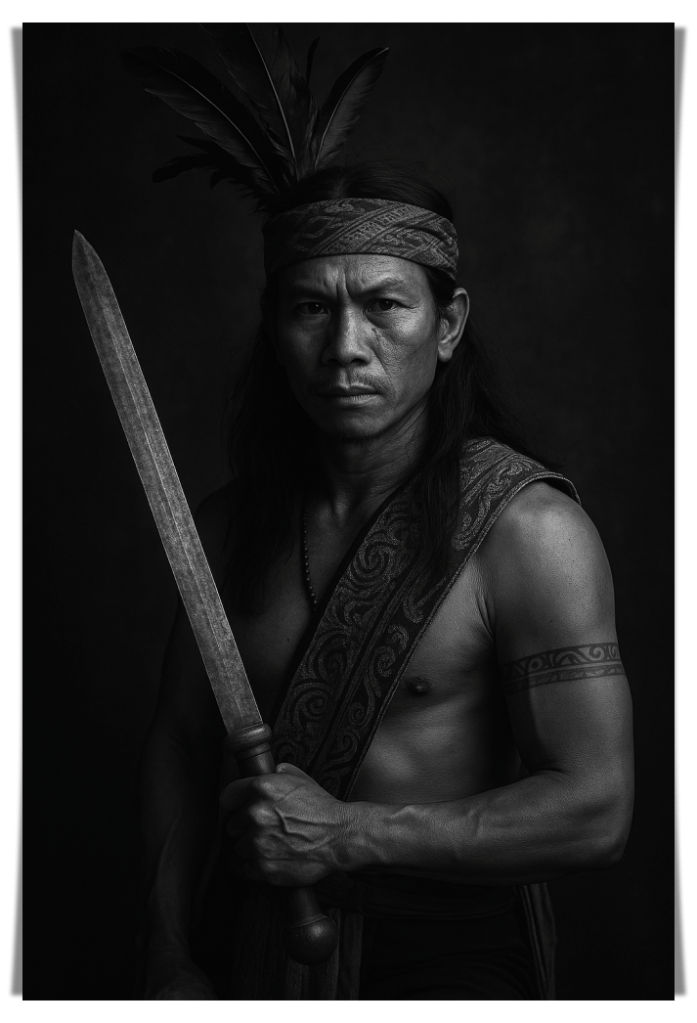

When I saw this prompt, I didn’t think twice. My favorite historical figure isn’t from faraway lands or great empires. He is my ancestor, Orang Kaya Pemancha Dana Bayang (or Dana Bayang), the legendary Iban war leader of the early 19th century.

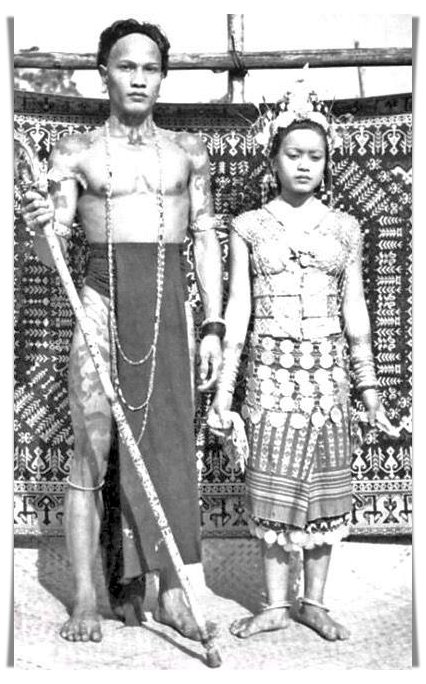

Dana Bayang was from Padeh, a longhouse upriver in the Saribas. In addition to his prowess in battle, he was renowned for his ability to guide his people wisely at a period when preserving their way of life from both local and foreign dangers was essential to their survival. His warriors, loyal and fearless, served as the first line of defense. Among them was Sabok Gila Berani, his right-hand man who eventually established our longhouse (village), Stambak Ulu. Stambak Ulu was a strategic sentinel, not just a village. It sat along the river, watching for enemy warships approaching up the Layar. From there, word could be quickly transmitted upriver to alert Dana Bayang in Padeh. Stambak Ulu became a shield, protecting Dana’s people and territory.

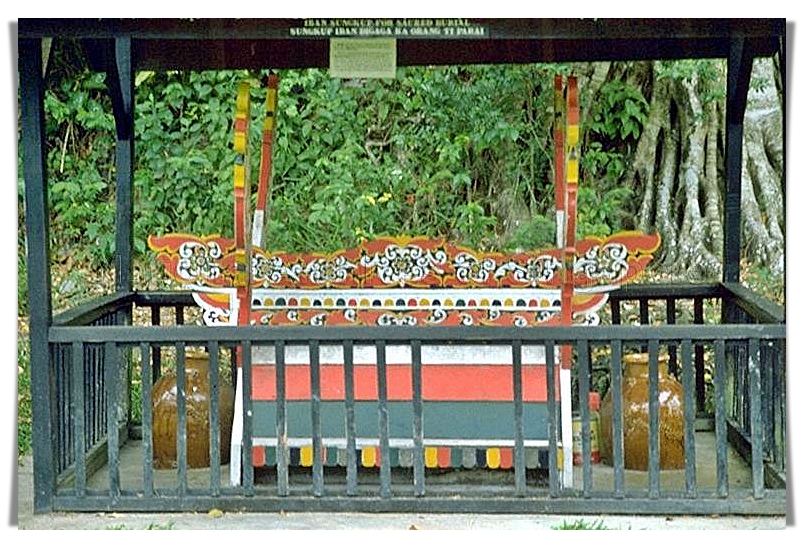

Years later, Sabok’s son Mang adopted Dana’s granddaughter, Mindu—my great-great-grandmother—after her father, Aji, Dana’s successor, was defeated by Charles Brooke’s forces in 1858. Aji’s death was a turning point, as the old ways clashed with colonial ambition. Mindu’s mother, Dimah, died soon after, leaving her an orphan.

When I think of Dana Bayang, I think of courage that was not for glory but for the preservation of a way of life, of the land, spirits, and community. His sons and warriors fought to keep their people free, to defend their beliefs, customs, and homeland. Nonetheless, they stood on the edge of change as the White Rajah’s army (colonialism) drove into Sarawak’s heart. The story of Dana and his warriors reminds me of what it means to belong to a people who refused to give up, who carried defiance and hope in equal measure.

You can even catch a glimpse of Dana Bayang in the 2021 Hollywood film Edge of the World, which offers a sneak peek of Brooke’s voyage of discovery to Sarawak in the 1800s.

This reflection ties closely to something I wrote earlier: Inheriting Courage From My Warrior Ancestors. The courage I speak of is not just in legends; it lives in the bloodline, in memory, in the quiet resistance of holding onto who we are.

A Chieftain’s Lament

Between the ritual’s demand and the crown’s decree

my once-steady hands falter in silence.

The nyabur rusts in my palm,

steel thirsting for blood,

now hushed by law.

The earth splits open—

Brooke’s foreign feet press into its cracks.

I hear signs, I dream dreams.

We need fertile grounds.

Blood must avenge blood.

But Brooke tells me to sheath my hunger,

swallow the sun, unlearn the hunt.

He asks me to bow, to bury my blade—

yet the wind whispers of battles still untold.

A fire stirs in the pit of my chest,

a pact with shadows, ancestors long gone.

Can we silence our spirits, break our bond?

Or will the old gods rise in the dust of our revolt?

I smell old skin burning,

the wild call of crows—

but I am chained to the unseen leash of kings

who promise peace with chains.

Note:

Nyabur – curved sword from Borneo, a headhunter’s weapon

©2024 Olivia JD

Olivia Writes offers printables, templates, and art designed to inspire reflection, healing, and creativity. Visit Olivia’s Atelier, Redbubble, and Teepublic for more.