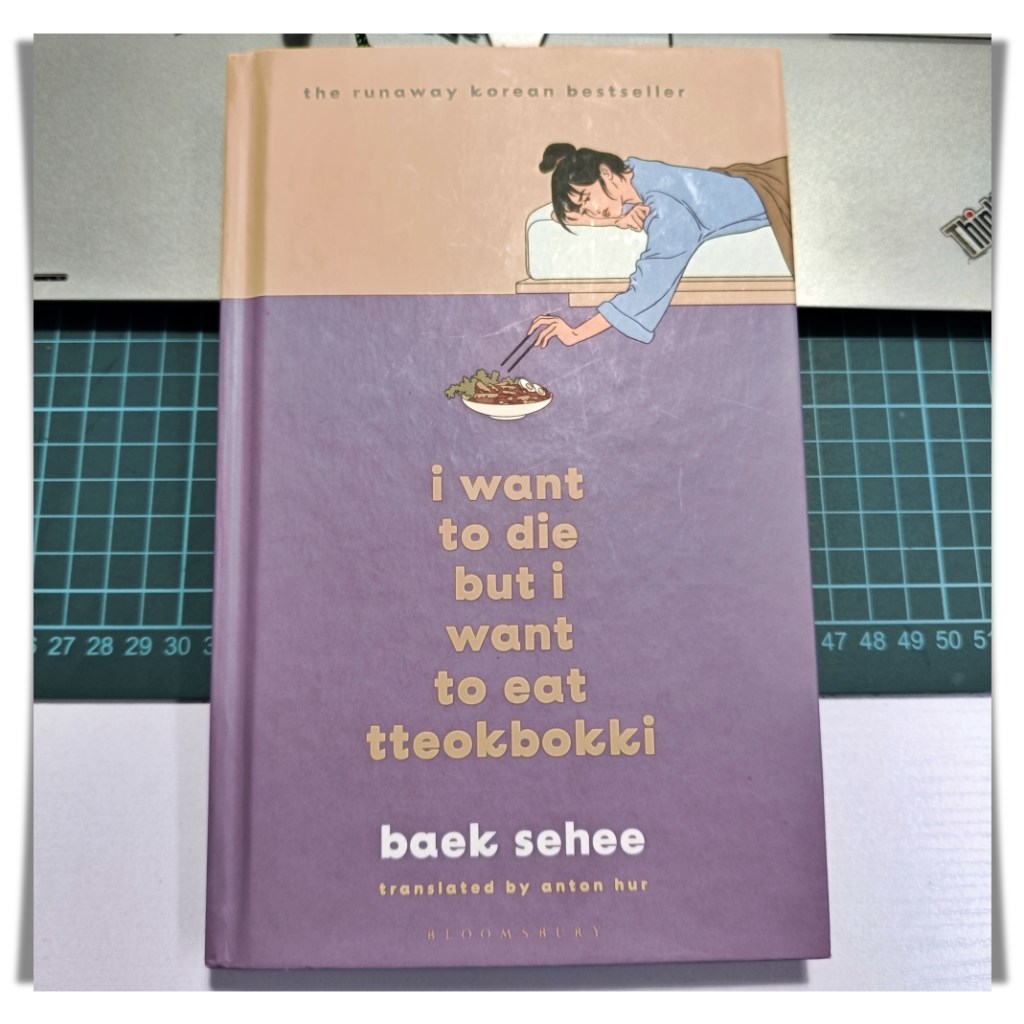

I discovered Annie Ernaux’s writing pretty recently and at a time when I was learning to trust my own voice. I’ve been writing for a long time, but apart from blog updates, I almost never published my work. (I published 4 poems in online literary journals last year). Though I love writing, I spent the last 15 years focusing on my art, pushing writing to the back burner.

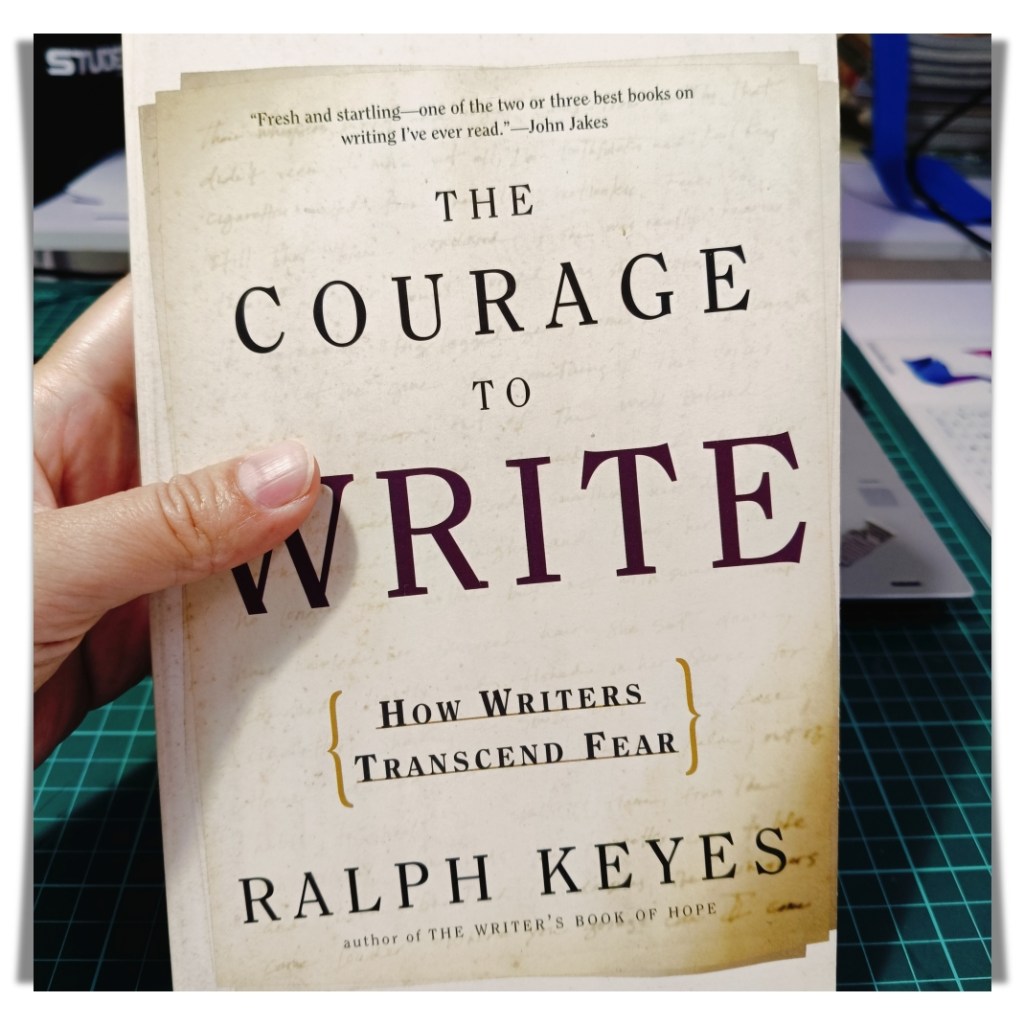

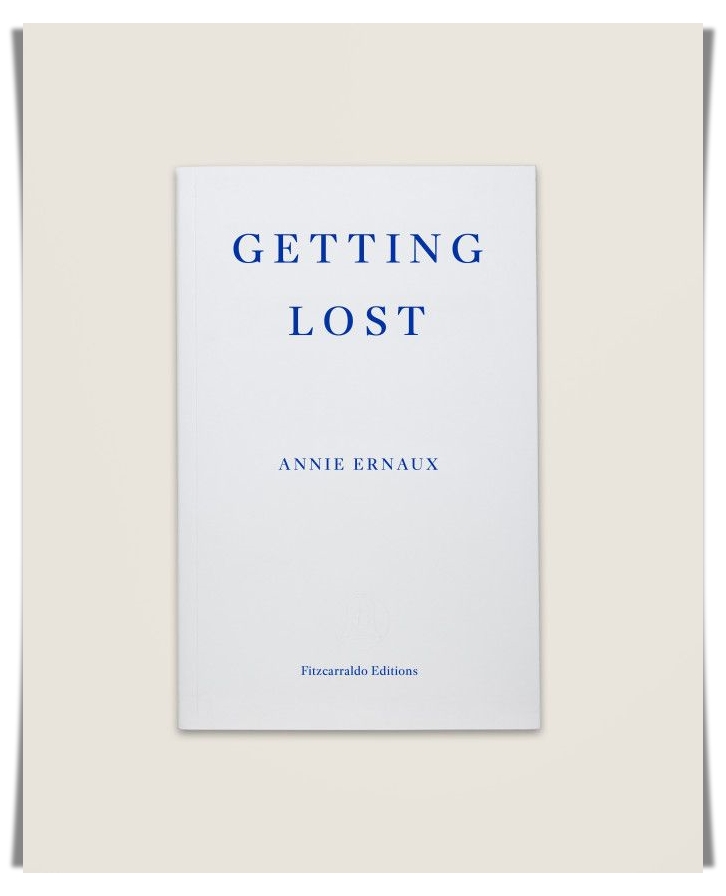

Image source: My Everand subscription

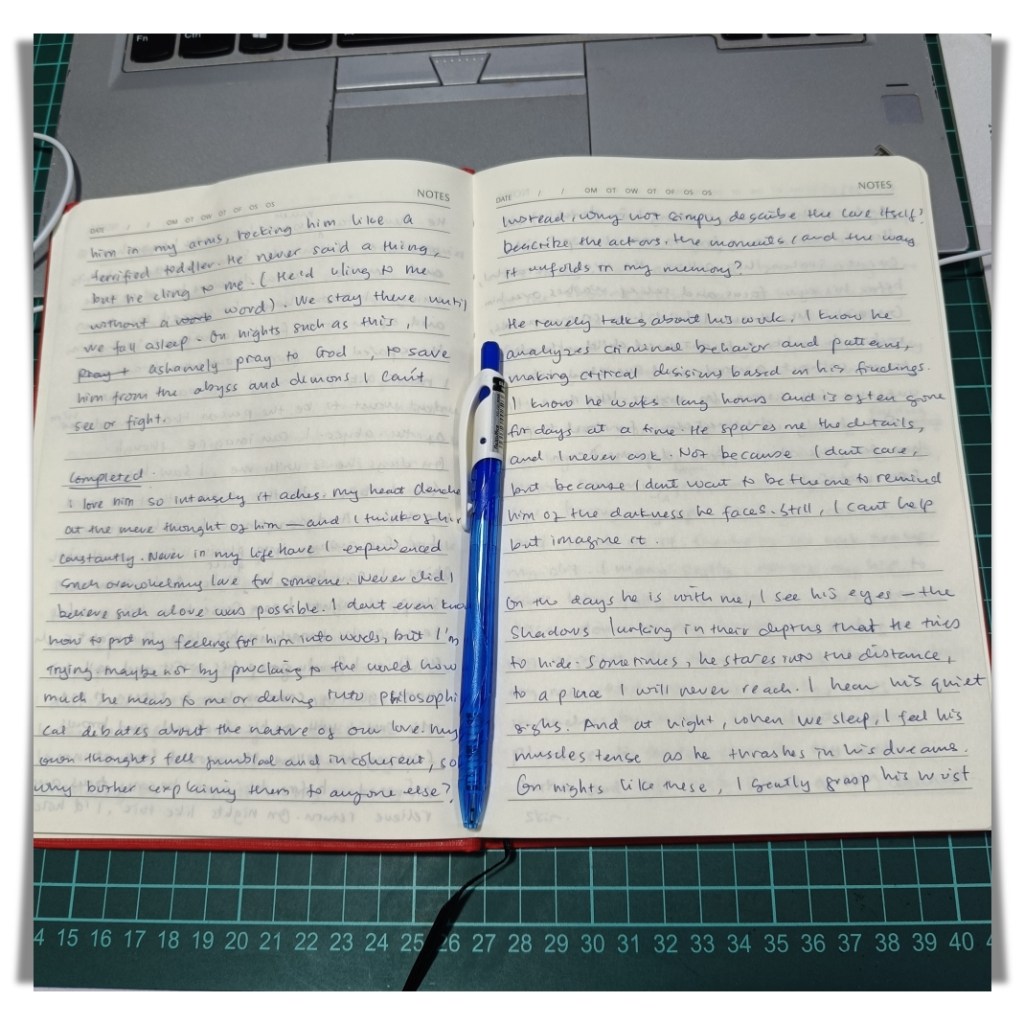

I write poetry and short stories now and then. They are nothing grand or serious because I don’t feel compelled to write a whole book with a complete plotline and characters. I collected my short stories; some are purely fiction, and some are based on true experiences and stories. I have never met anyone who writes like me until I came across Annie Ernaux’s work.

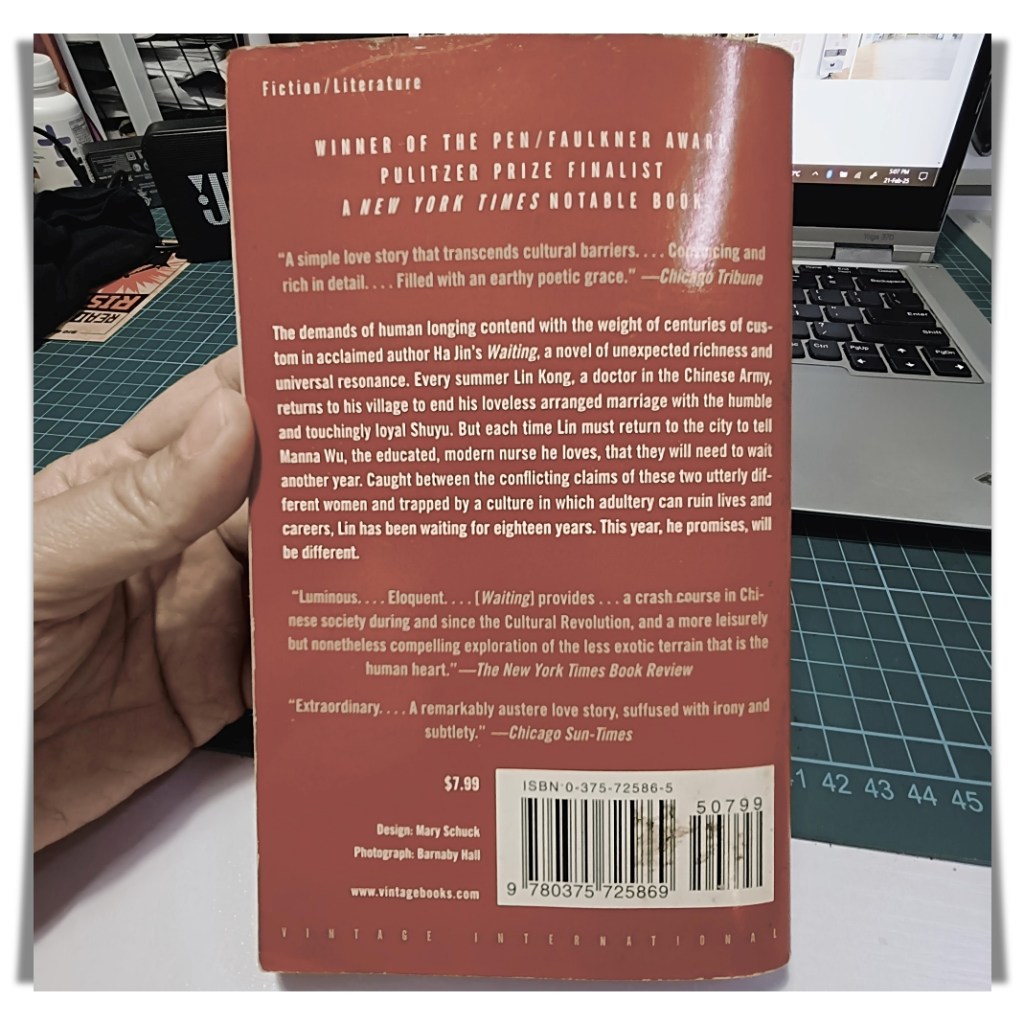

Reading Ernaux was like finding a mirror I never knew existed. Ernaux, like me, dissects the past obsessively. She revisits memories repeatedly, searching for meaning in fragmented events of the past. But there was a difference I couldn’t ignore. Ernaux writes with a stark, almost clinical detachment. She lays out the details of her life as if she is simply recording facts. She does not romanticize or dramatize; she just records the experiences. Her writing reads like an autopsy of the past, as if she had already processed it, wrapped it up, and put it on a shelf labeled “This happened in the past.” She records the details of her love affairs, including the lurid moments, without nostalgia, shame, or guilt. This is what she wrote about one of her lovers:

“The man for whom I had learned them had ceased to exist in me, and I no longer cared whether he was alive or dead.” ~ Getting Lost

And that, I realized, is where she and I diverge.

I don’t just remember the past—I relive it. Every emotion returns, undiluted by time. I don’t just recall what happened; I feel it as if it’s still unfolding inside me. The joy, the pain, the longing, the grief—they rush back in full force. Because of this, my writing is anything but detached. When I write essays, blog posts, poems, or stories inspired by past events, they carry the pulse of my emotions. They are raw and undiminished. And for a long, long time, I felt ashamed of my voice and lacked confidence in expressing myself. I thought that was a flaw.

Image source: My Everand subscription

I admired Ernaux’s ability to write without apology or hesitation. I wondered if I needed to learn detachment and strip my words of emotions so they could be seen as more “literary” and taken more seriously. After all, isn’t that what makes writing powerful—the ability to observe without being consumed? But the more I wrote, the more I realized: I don’t have to be like her. I don’t have to sever myself from my emotions to be a writer.

I realized that I don’t have to strive to be as detached as Ernaux. I can learn to be confident in my voice and embrace my own way of writing. My writing is where memory stays alive, where emotions breathe between the lines, unfiltered, unsoftened.

My words do not have to be clinical to be valid. They do not have to be detached to hold power. I am learning to write without shame, guilt, and hesitation. I will not erase the emotions—I will let them exist freely.

Perhaps I will never reach the kind of distance Ernaux has from her past. But that’s okay; my voice is mine, and it is enough.

So I wonder—must we detach from memory to write about it? Or is feeling everything deeply has its own power?