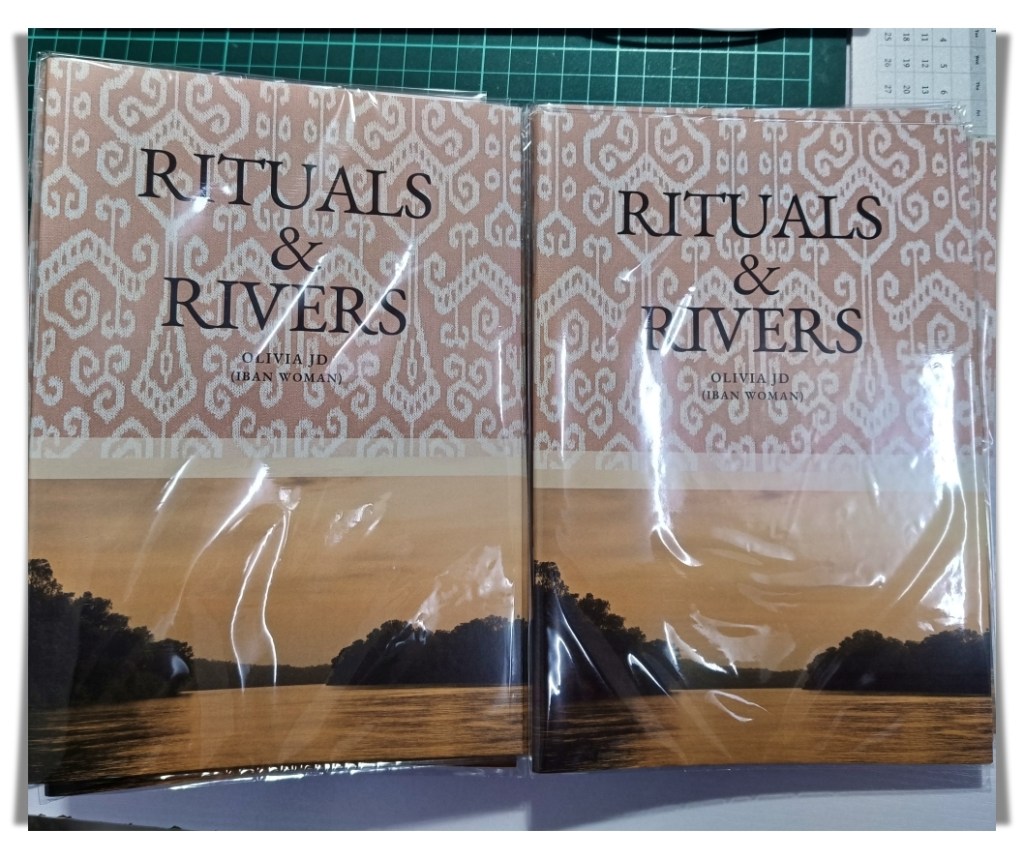

Tomorrow is the soft launch of Akar Kita Abadi, the group exhibition I’ve been preparing for the past few weeks. I will exhibit several of my Iban heritage poems called Rituals and Rivers, and holding these printed booklets, which just arrived, feels like a confirmation of all the time spent writing, editing, and polishing. This little booklet (or zine) has 10 poems from a much bigger collection of Iban heritage poetry that I want to publish in 2026. I will be selling these booklets during the exhibition and they are quite limited in number. I will share more about the exhibition after the launch tomorrow. I can’t share pictures until after the launch so I can’t really say much about the whole thing. The exhibition will last until 23 November so if you’re in Klang Valley, you may want to drop by and give us your support.

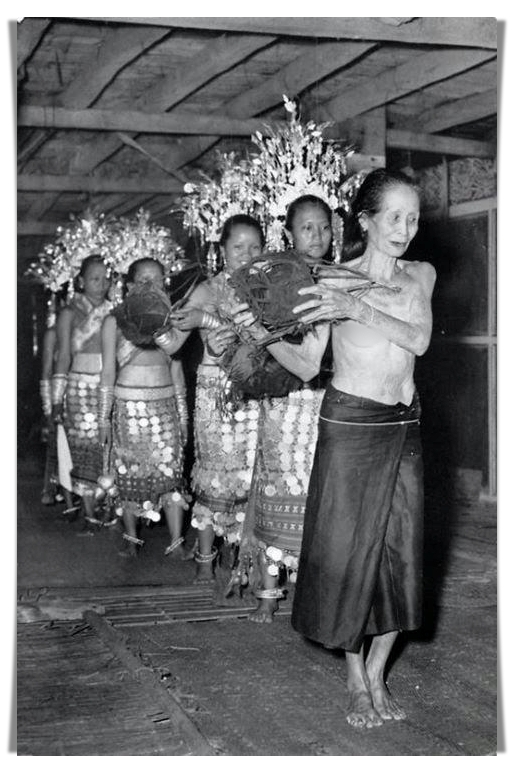

While this exhibition marks the beginning of sharing that collection publicly, another project has started to take root in parallel. I have begun working on a new zine that will focus entirely on Iban women. This project seems like a continuation of Rituals & Rivers, but through a more personal viewpoint. It will look at various facets of Iban womanhood, from ancient times to the present.

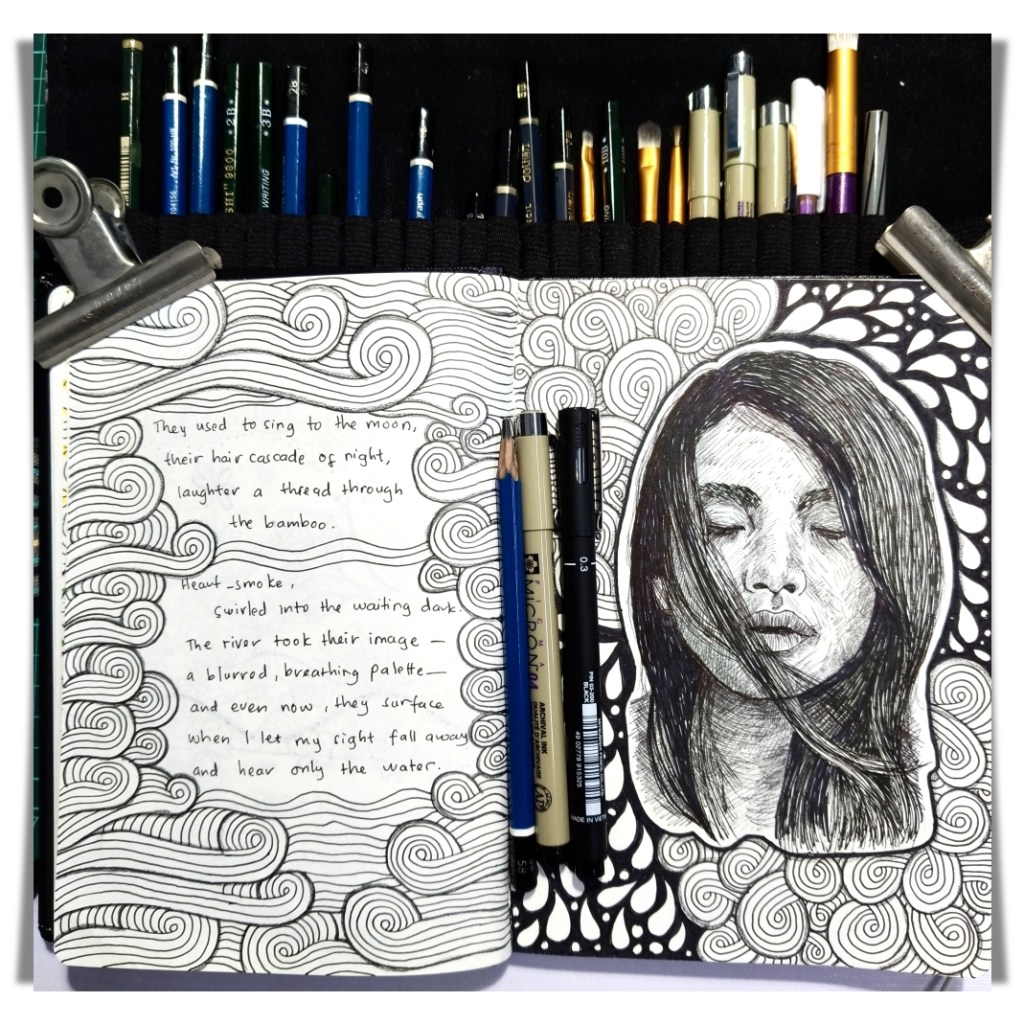

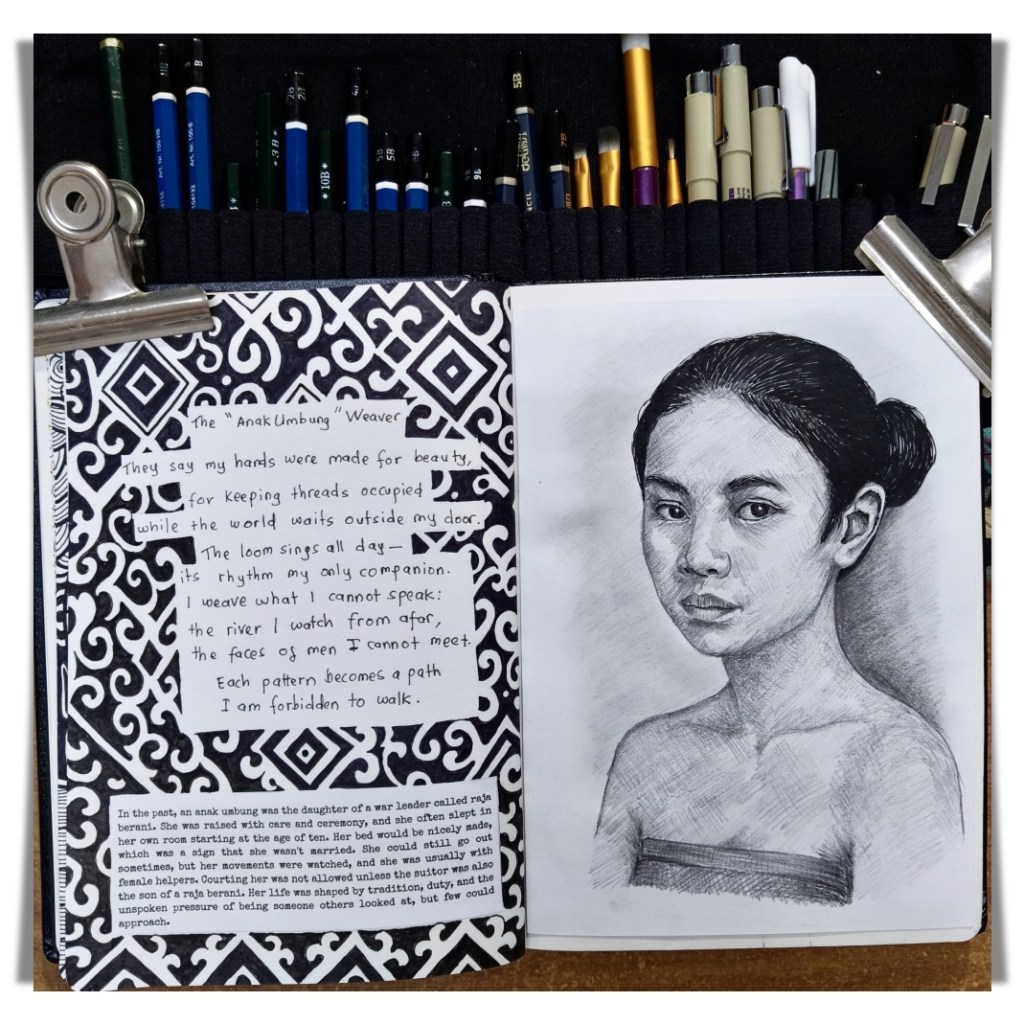

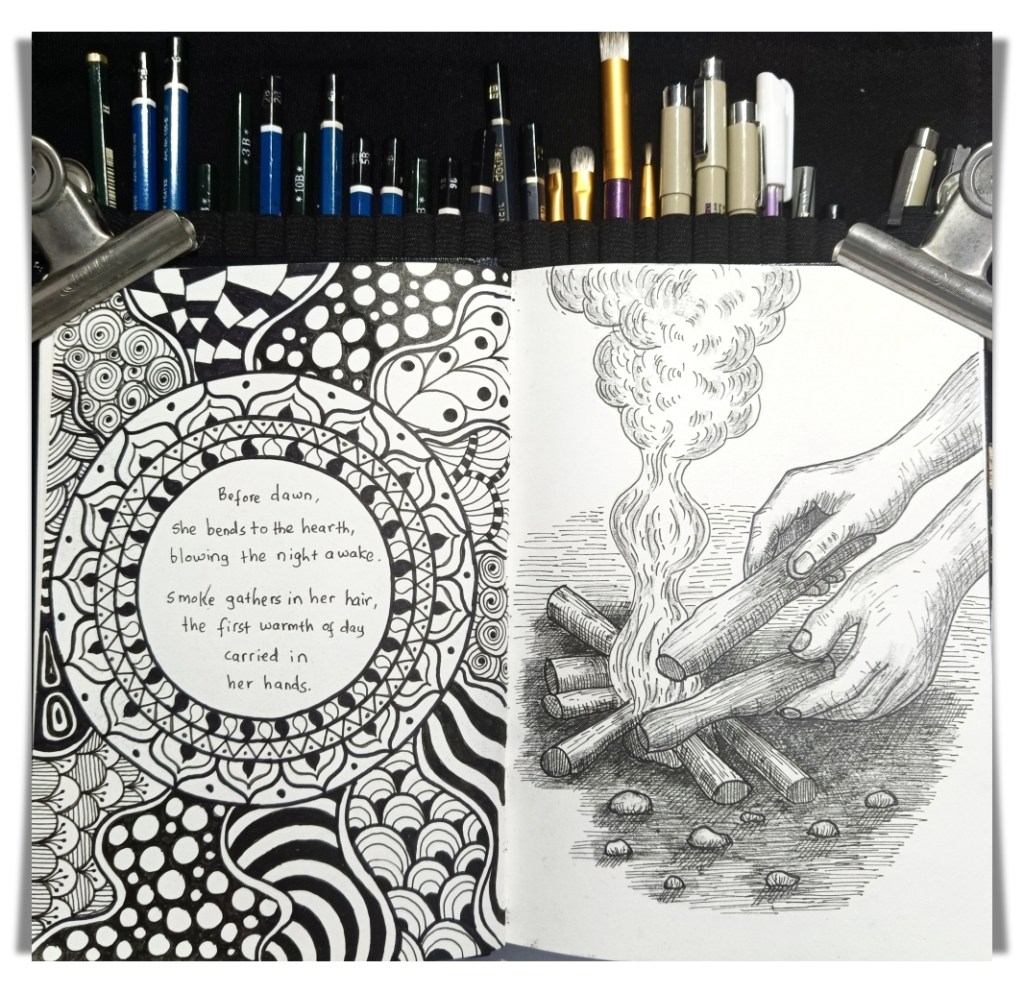

Every page will be hand-drawn using pencil and black fine liners, but for the actual zine they will be edited and printed. Drawing by hand has a grounding effect, allowing each line to have its own rhythm and imperfection. The only printed text will be the longer passages and explanations, saving space while keeping the design balanced. I have not planned the number of pages or illustrations yet. I like to let the process evolve spontaneously. Each piece generally begins as a poem or a brief reflection before taking on a visual shape.

One of the first illustrations is inspired by women who sing to the moon as their laughter threads through the bamboo. Another drawing shows the anak umbung, the daughter of an Iban war leader who was raised apart from others and taught weaving skills. Her story has stayed with me, serving as a reminder of the beauty and self-control that once entwined women’s lives. There is also a drawing of a woman tending to the hearth before dawn. These aren’t big moments; they’re small actions that show tenderness, duty, and strength in Iban women.

This new zine will be based on the same ideas as Rituals & Rivers, but it will focus more closely on the daily and the personal. It will explore what it means to be an Iban woman across generations, including the traditions that are passed down, the unspoken resilience, and the actions that connect one life to another. It’s a way for me to listen to the voices of the women who came before me and to honor how their spirit still lives on in us now.

I don’t know what the completed zine will be like, but I know it will develop slowly, page by page, just like stories used to do, with care and patience.

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.