Books are expensive in Malaysia. Anyone who reads a lot already know this. A single paperback can cost as much as a meal for two people at times. And when you’re trying to pay your bills, parenting, buy groceries, or just get through the month, buying a new book feels like a luxury that’s easy to postpone.

That’s why I’ve always liked used bookstores. Yesterday I went to a small, quiet bookstore in Subang Parade called BFBW – Books for a Better World. I wrote a short post about it on Threads, but the visit stayed with me. The variety of titles and the reasonably priced books weren’t the only factors. It was the mood and what the place stands for.

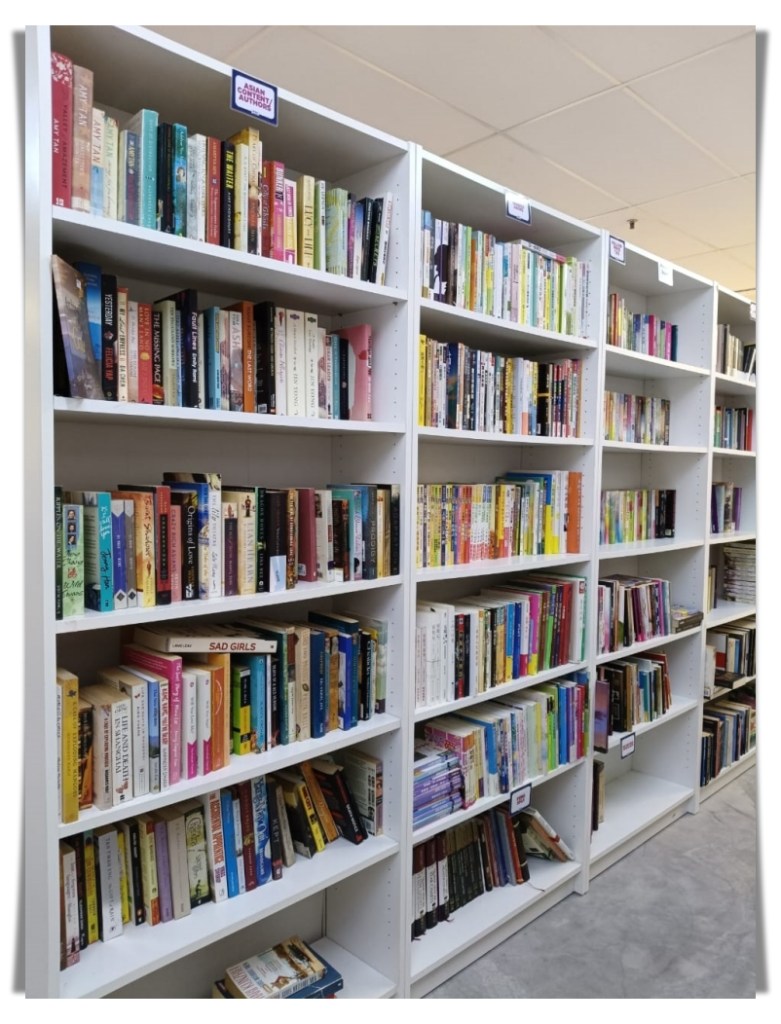

The bookstore is small. There aren’t any cozy corners or mood lighting for photos. There were just clean white shelves, a blue donation box with a cartoon bear on it, and fluorescent lights above. There were no frills in the room, and the floor was just cement. But it still felt good, simple, welcoming, and real.

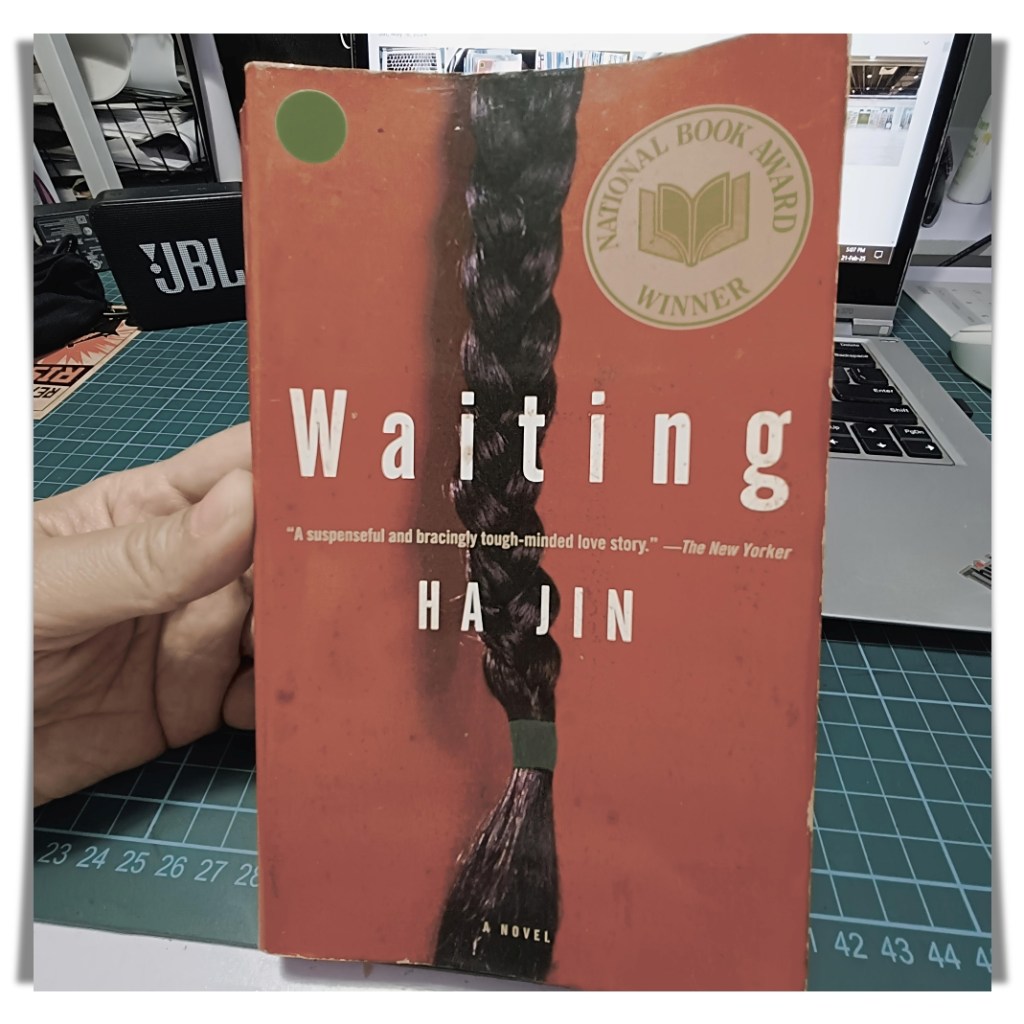

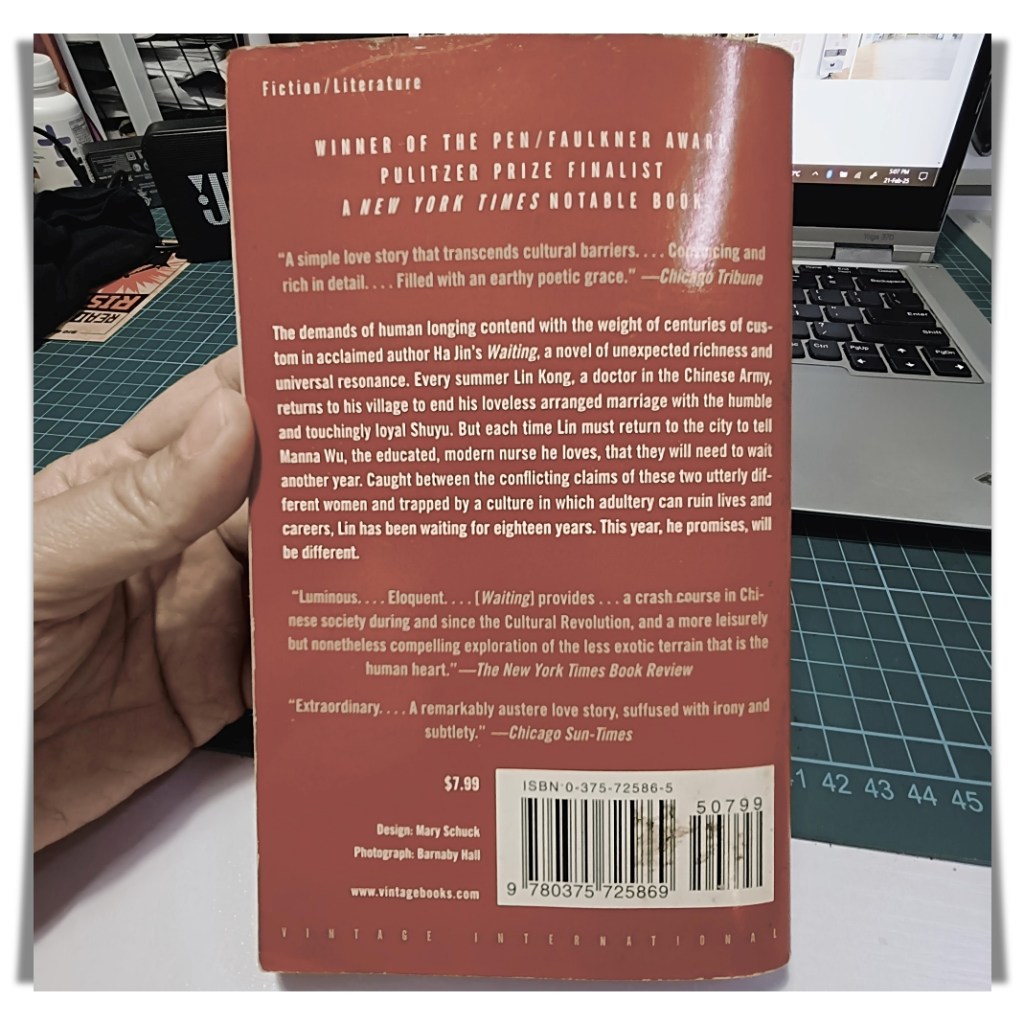

What made it feel meaningful was the sense that every book had already lived a life. Each one had been read, or maybe left unread, carried in someone’s bag, or left waiting on a nightstand. They were now waiting for someone else to bring them home. That continuity, stories passed from person to person, makes used books unique and special.

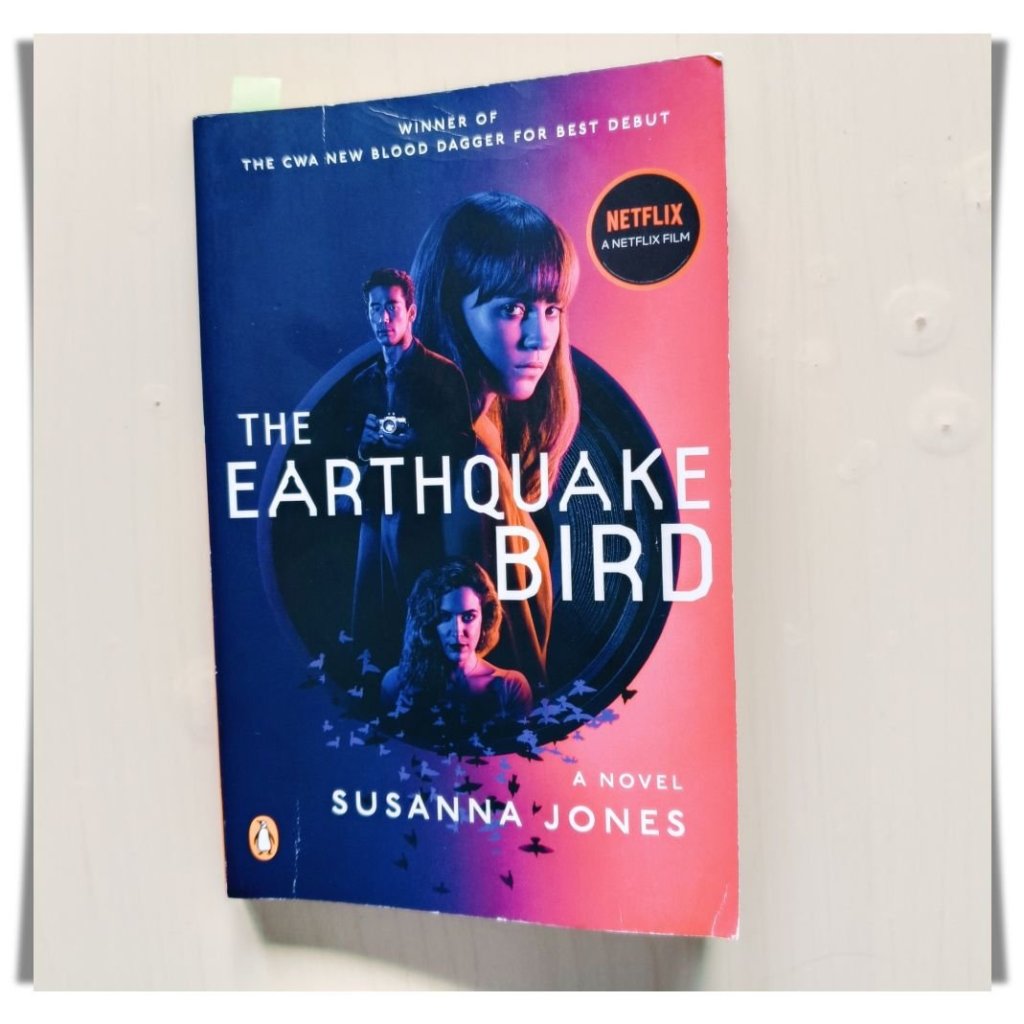

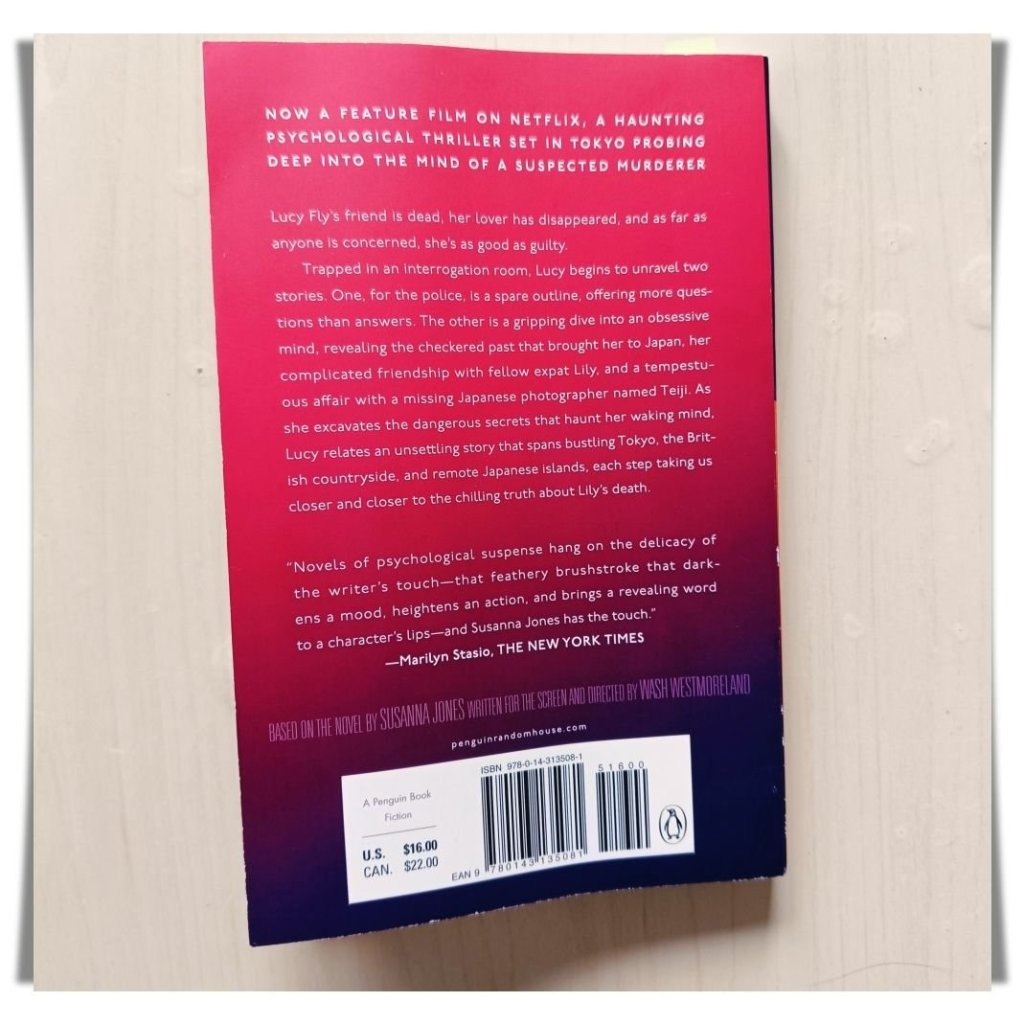

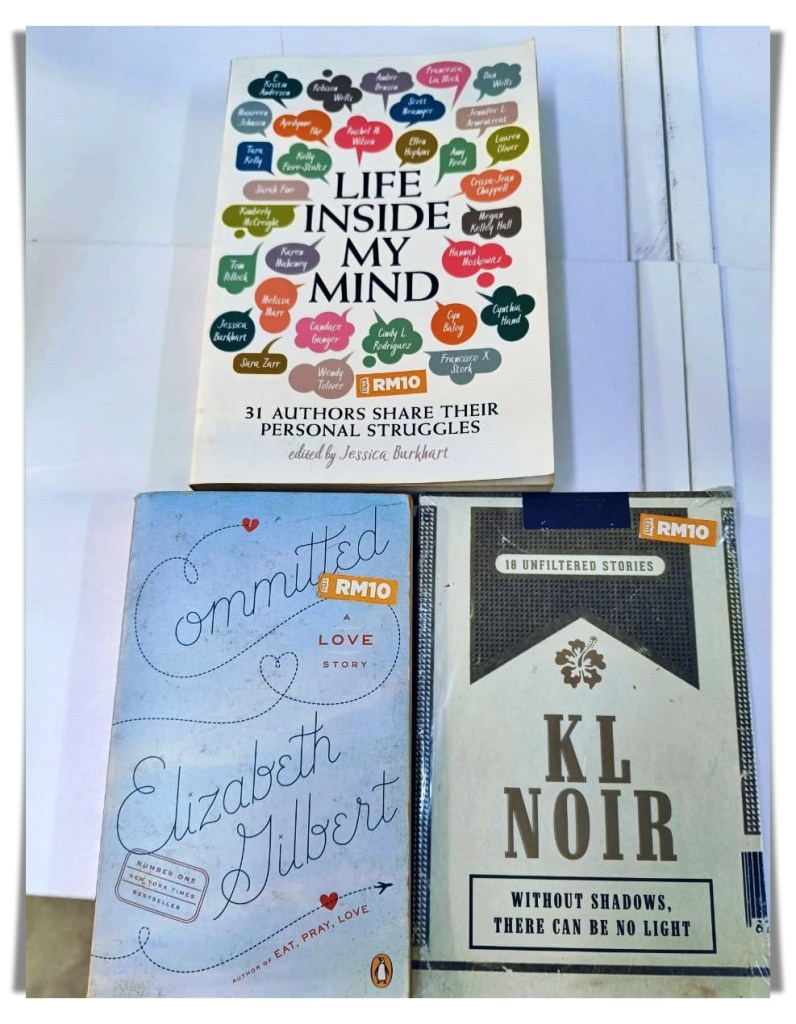

I ended up buying three books for RM10 each. One was Committed by Elizabeth Gilbert, which I’ve wanted to read for a long time. KL Noir was another one that caught my eye because of its subtitle: “Without shadows, there can be no light.” The last one was Life Inside My Mind, a book of essays by different writers about mental health. That one hit home.

These books weren’t in perfect shape. One had corners that were folded. The edges of the other one had faded. But that didn’t matter. I liked that they had been somewhere before me. Someone else had opened these pages and read them, or maybe they didn’t. It’s possible that the book was passed on without being read. It had traveled in any case.

That’s one of the little things that make used bookstores so nice. When you buy a book, you’re getting more than just a book; you’re getting a piece of someone else’s journey. It gives the book a deeper meaning that new books don’t always have.

At the front of the store, BFBW also has a donation box where people can leave books they don’t need anymore. The donated books aren’t just sold again; they’re also given to literacy programs and charities. Communities, schools, and small libraries benefit directly. It’s a simple system that supports access to reading.

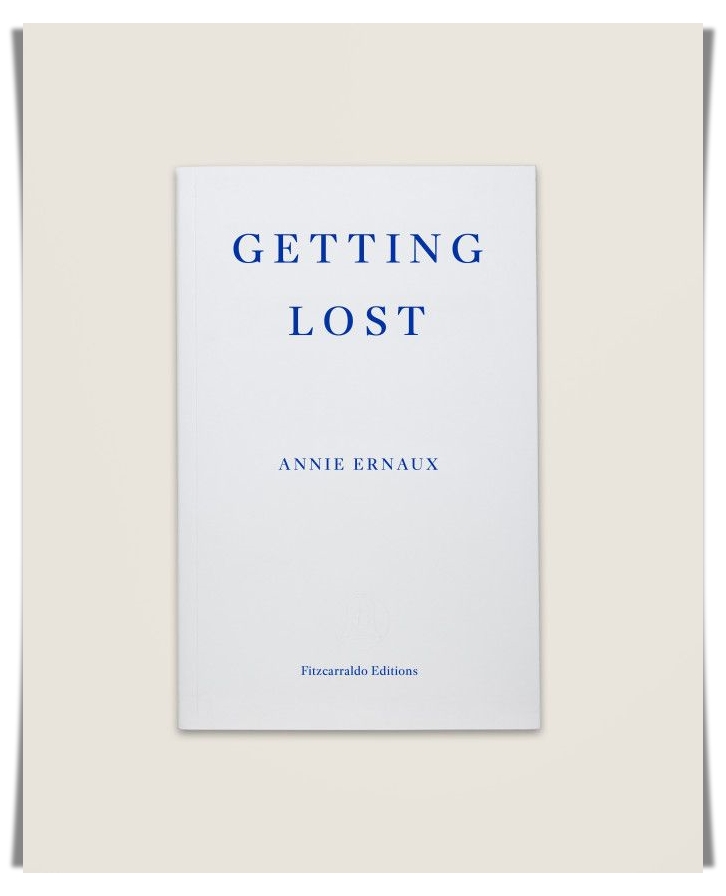

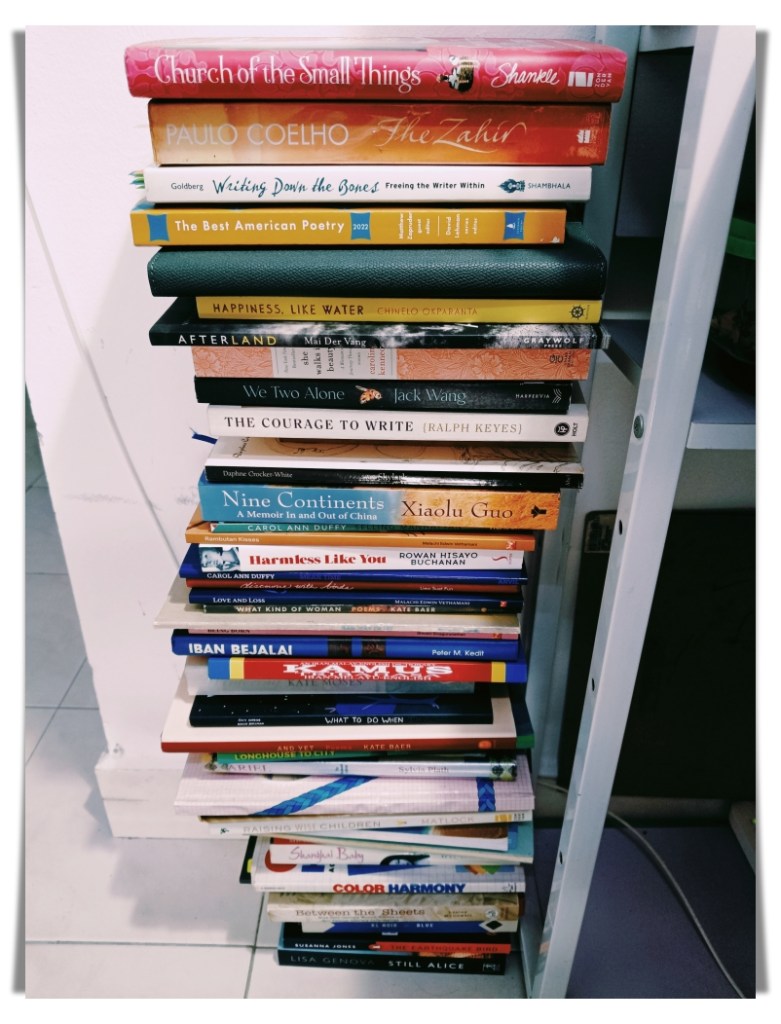

While standing there, I reflected on my own bookshelves at home and the books I have kept but no longer read. Some of those books meant something to me at one time, but now they’re ready to go. I also bought books on a whim and never read them all the way through. I realized that giving them away could give them a new life.

It reminded me that sharing stories is more than just writing and publishing. It’s also about letting go and letting a book continue its journey by giving it to someone else. By letting go, we are passing on what helped us in the past or what we never got around to reading.

As a mother and a writer/artist, I often think about the kind of legacy I want to leave behind. This includes not only my own work but also the values I pass on. I want my kids to grow up in a world where they can get their hands on books. Where knowledge and imagination aren’t limited by price and where stories travel. Bookstores like BFBW make that vision feel possible.

If you live in the Klang Valley and have books that are in good shape, whether they are fiction, nonfiction, or children’s books, think about giving them away. Or take a little time to look around and pick up a few. You might find something you didn’t expect. You might rediscover the joy of reading without pressure.

I’m glad I stopped by. I left with three books and the feeling that I was part of something bigger. You are not just a reader but a link in a generous chain of people passing stories along. It really is that simple sometimes.

Olivia Atelier offers printables, templates, and art designed to inspire reflection, healing, and creativity. Visit Olivia’s Atelier for more.