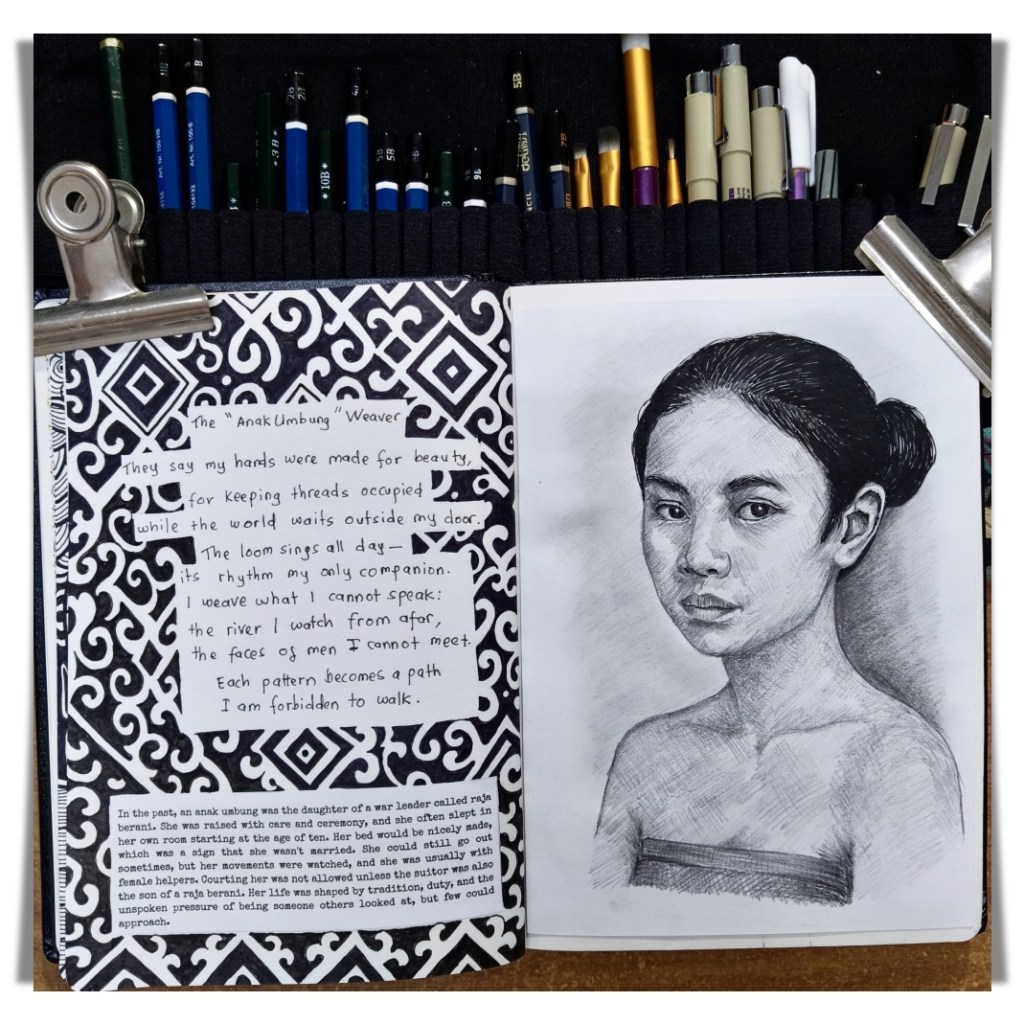

Among the Iban, weaving has always been a measure of a woman’s place in the community. The knowledge is passed down from mother to daughter, usually when a girl enters her teenage years. She learns each stage with patience: preparing cotton yarn, tying the threads, selecting designs, and working through the complex dyeing process. Every step includes a ritual to maintain balance with the spirit world. A weaver must be skilled, but she must also be spiritually open in order to progress. Through weaving, she learns how to approach the unseen forces that shape her life as a woman and as an artist.

A weaver must follow the traditional sequence of learning. If she attempts skills before she is ready, she risks falling into layu, a state of spiritual deadness. Elders say this condition can affect both the mind and body, and once it takes hold, death is believed to be the only release. Every Iban woman understands this danger, so she approaches her craft with devotion and deep caution.

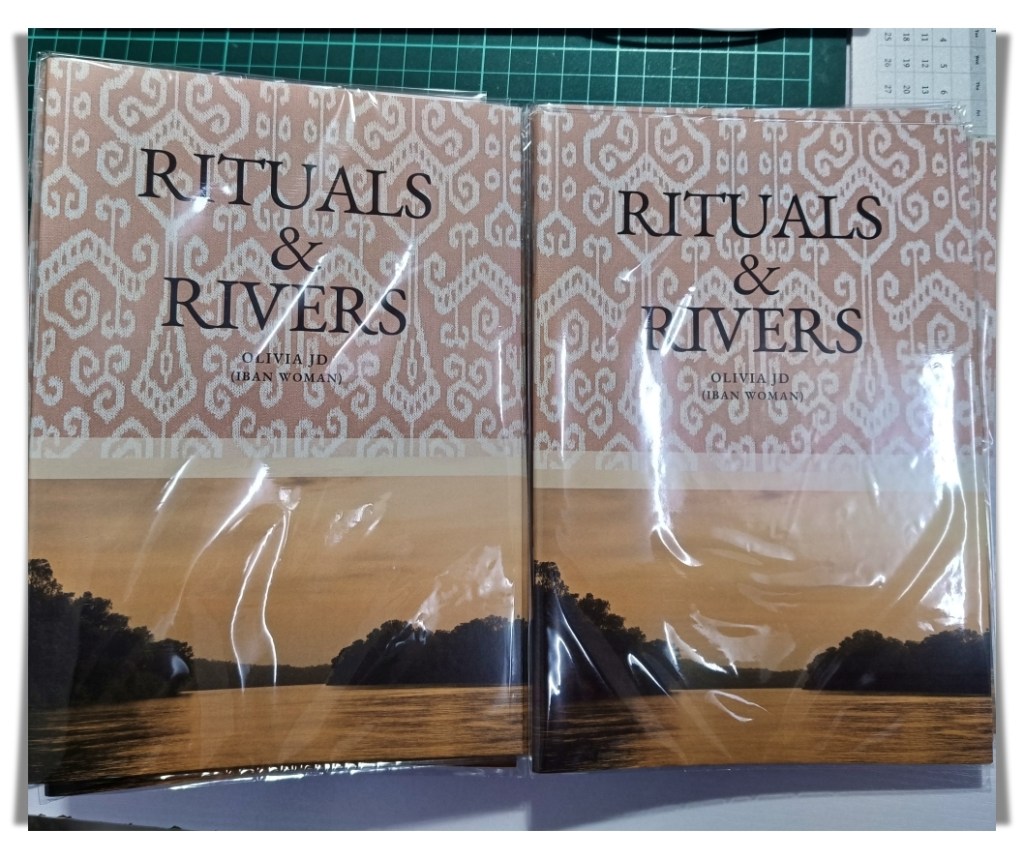

Pua kumbu is a way to understand a woman’s status. Her rank depends on the dyes she uses, the complexity of her patterns, the precision of her technique, and her relationship with the spiritual world. A pua is not judged by beauty alone. It reflects the weaver’s inner state, her discipline, and the spiritual guidance she receives. Even though many Iban families today have adopted modern beliefs, the traditional criteria for judging a pua still hold meaning. The rituals and techniques behind each piece continue to define its value.

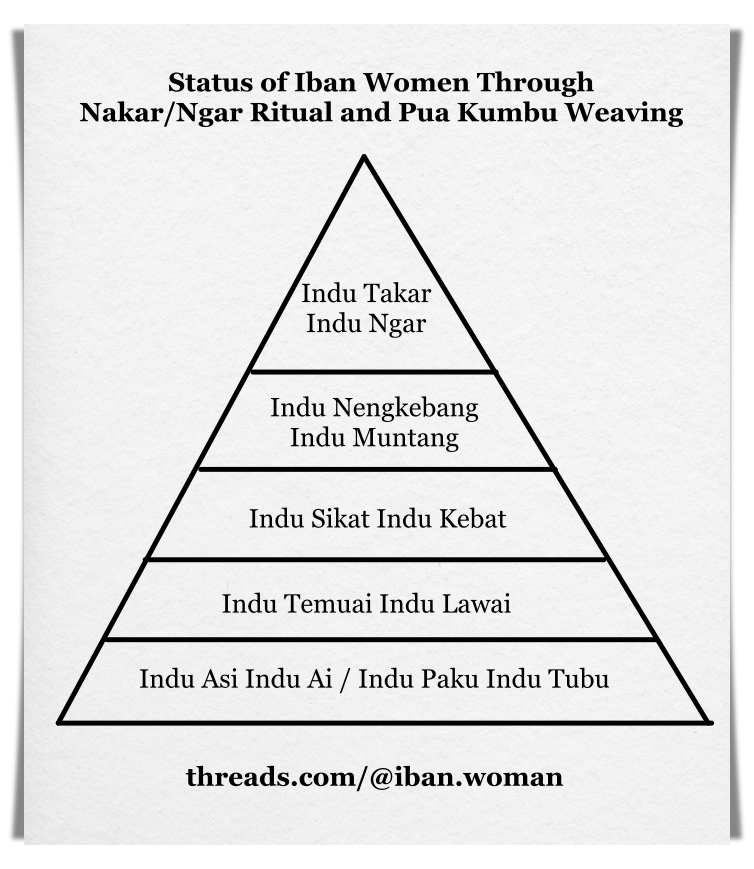

There are several ranks within the weaving world. At the first level are women who do not weave, called Indu Asi Indu Ai or Indu Paku Indu Tubu. They may not come from weaving families or may lack the resources to learn. Much of their time is spent farming and managing household life, and they cannot afford the labour or materials needed for weaving.

The next group consists of women known for their hospitality, called Indu Temuai Indu Lawai. These women usually have enough rice, help, and stability to weave simple designs. With guidance from others, they can produce basic patterns such as creepers or bamboo motifs.

A novice learns within strict boundaries set by tradition. She begins with a small piece of cloth and a simple pattern called buah randau takong randau. She may only weave a cloth that is fifty kayu in width. As her skills improve, she increases the width of her work. By her tenth pua, she will reach a width of 109 kayu. These rules are deeply respected, as they are believed to originate from the spirit world.

When a woman becomes skillful, she is known as Indu Sikat Indu Kebat. She can weave recognised patterns but cannot create her own. Her designs come from motifs passed down through her ancestry. If she wishes to learn new patterns, she must make ritual payment to a more experienced weaver in exchange for permission to use them.

A higher rank is held by the Indu Nengkebang Indu Muntang. She is able to invent new designs, often revealed to her through dreams. She has the ability to attempt complex and spiritually demanding motifs. Her community respects her greatly, and she wears a porcupine quill tied with red thread as a mark of distinction. Other weavers pay her well for new motifs.

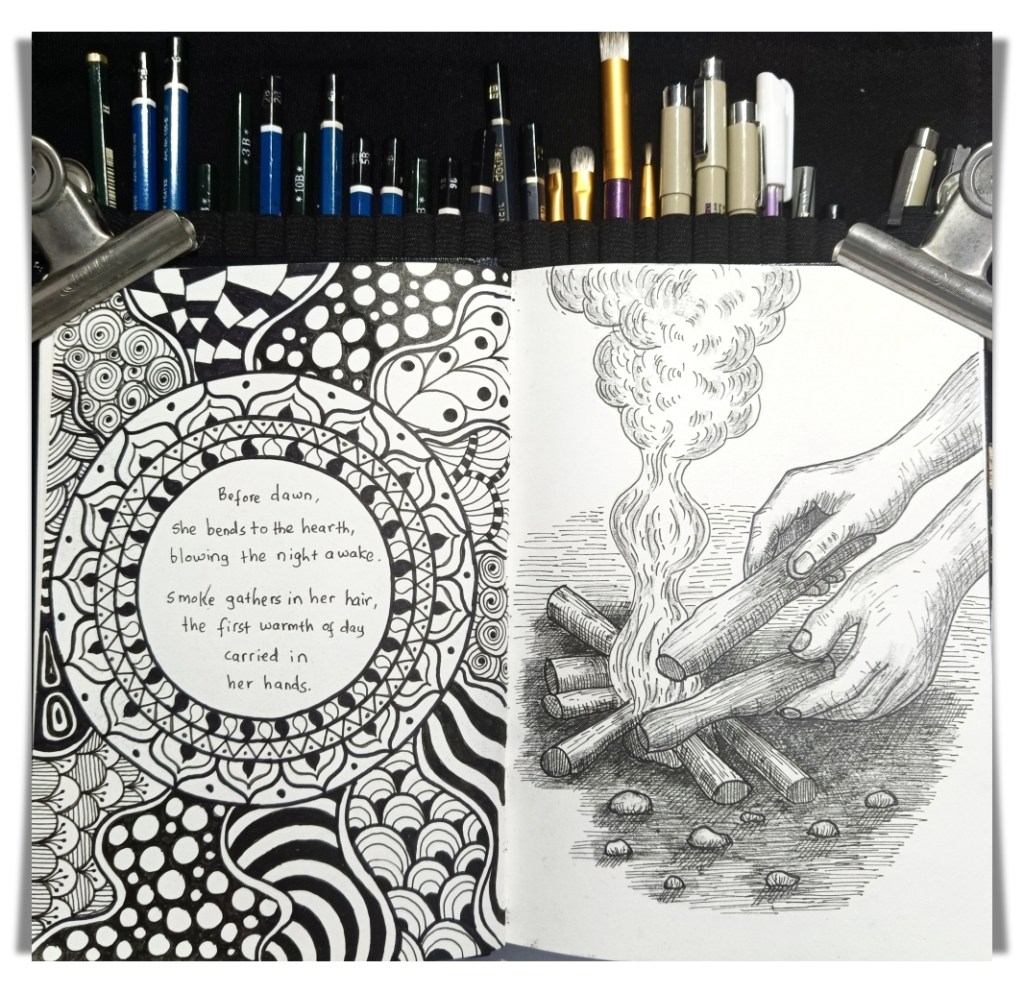

At the top of the hierarchy is the Indu Takar Indu Ngar. She is a master dyer, a master weaver, and a ritual specialist. She understands the exact balance of mordants and natural dyes and knows how to fix colour to cotton successfully. Many people know the basic ingredients, but only those with spiritual guidance can complete the process with precision. Her knowledge is both technical and sacred.

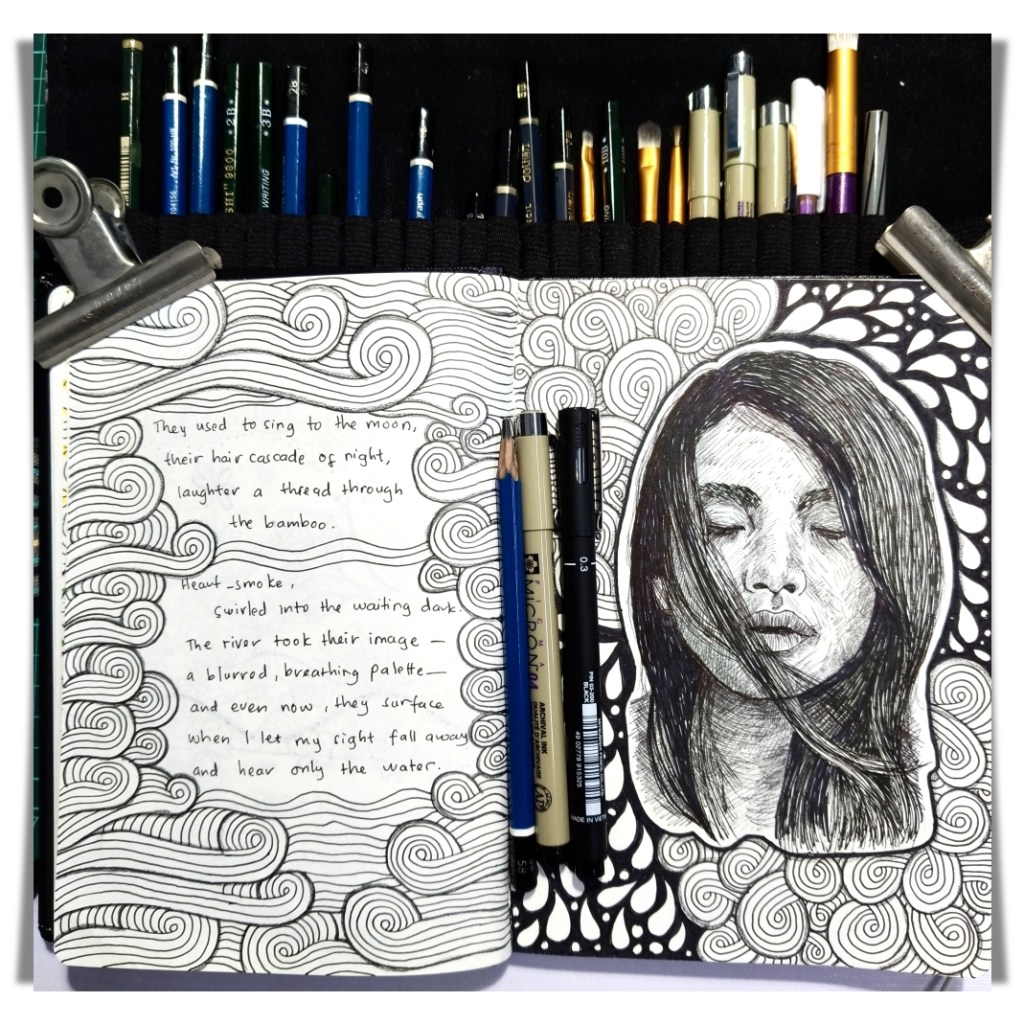

To reach this level, a woman must excel in all areas of weaving and dyeing. She must also receive recognition from the spiritual world. This acknowledgment often comes in dreams, which serve as both initiation and confirmation. Sometimes another person dreams on her behalf, affirming her role. Many women at this level come from long lines of weavers and dyers, inheriting designs, dye knowledge, charms, and the support of ancestors whose status once brought additional labour to their families. This allows her to devote herself fully to her craft.

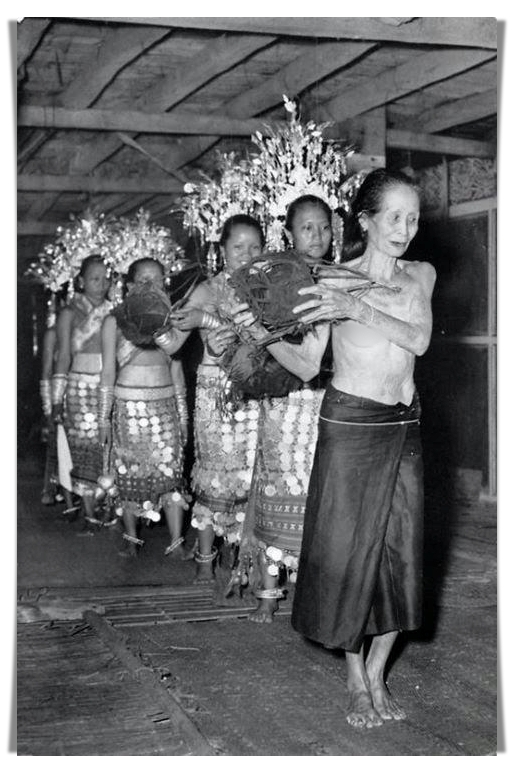

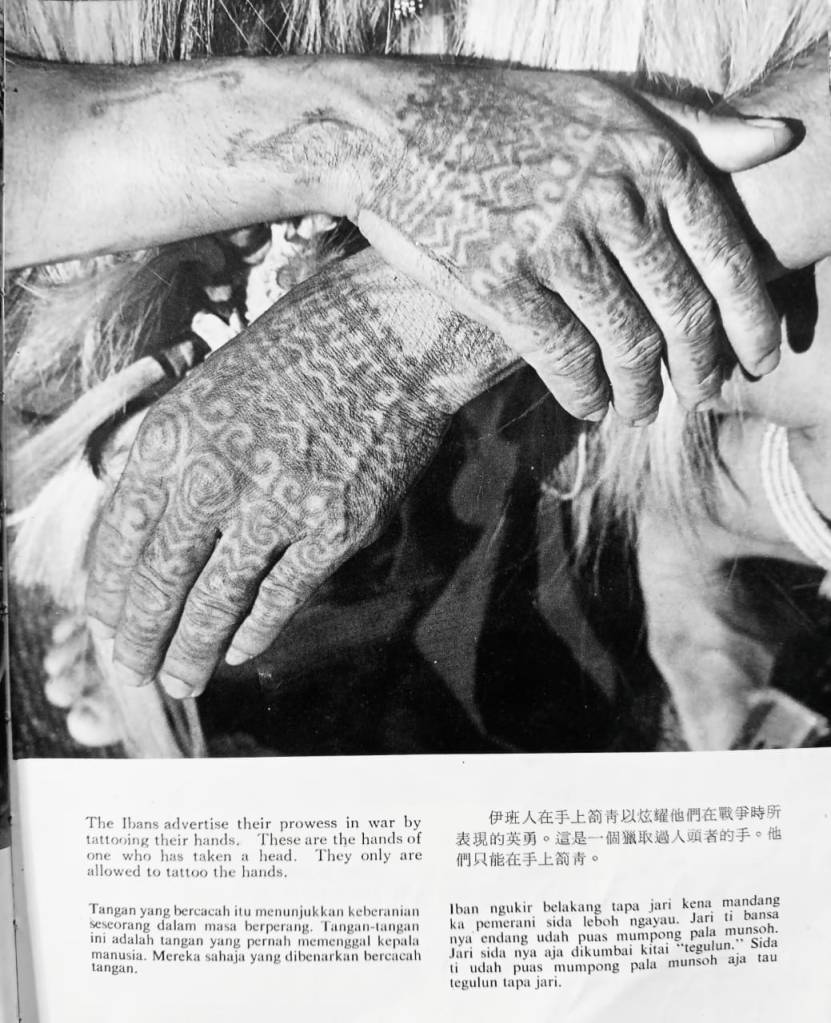

The Indu Takar Indu Ngar is responsible for the ritual preparations of the mordant bath. The ceremony includes animal sacrifice, offerings, and prayer. It is known as kayau indu, or women’s warfare. The ritual is private and demanding, and the leader must be courageous. If she loses control of the spiritual forces present, she risks falling into layu. Her bravery is regarded as equal to that of a warrior.

She also plays an important role in public ceremonies. During Gawai Burong, she scatters glutinous rice at the ceremonial pole. During Gawai Antu, she prepares garong baskets to honour the master weavers of earlier generations. When she dies, her funeral is filled with praise, and her worth is compared to that of a prized jar. Her husband receives honour as well.

Every pua kumbu carries the status of its weaver. Its complexity, width, ritual purpose, and intended use shape its value. Pua kumbu textiles accompany every stage of life and death for those who still observe traditional Iban practices. Each design is tied to a specific ritual, and the ritual gains its character from the cloth chosen for it. This is why pua kumbu remains central to the spiritual life of Iban women.

I write about Iban culture, ancestral rituals, creative life, emotional truths, and the quiet transformations of love, motherhood, and identity. If this speaks to you, subscribe and journey with me.