I didn’t grow up imagining myself as a mother.

Not as other girls did, pretending to cradle dolls or writing baby names in the margins of their schoolbooks. I wasn’t opposed to becoming a parent; it simply didn’t feel urgent, like something I needed to pursue or prepare for. And yet, I am here. It’s been years. A mother. With gentle hands and a heart that is always rearranging itself around little lives.

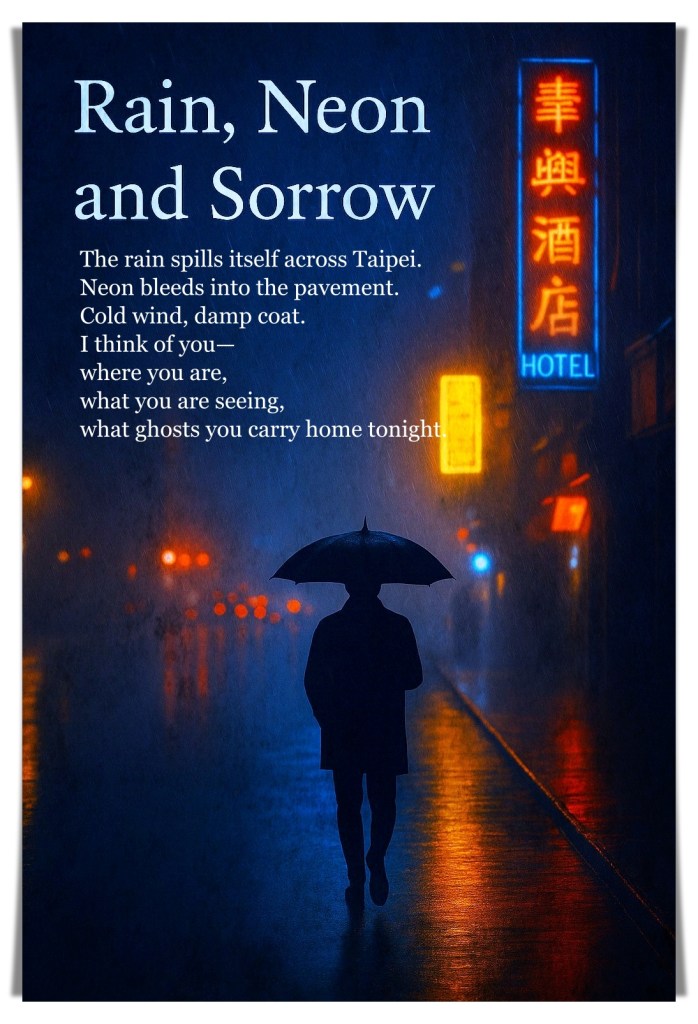

Mother’s Day used to pass with little thought. A day spent playing cards and making phone calls. Of seeing my own mother from a distance, attempting to decipher the aspects of her that I could never fully grasp. I had no idea she felt so invisible at the time. When you’ve given everything to others and lost yourselves, silence may be deafening.

Now I do.

Mother’s Day is now a quiet occasion in our family. The kids sometimes remember and sometimes they don’t. My hubby asks what I want to eat. I fold the laundry and do the dishes anyway. Life does not stop simply because it’s May. However, a part of me always wishes for a pause, if only for a moment. A pause that says, “We see you. It is not simply what you do, but who you are underneath it all.”

This year, I didn’t request flowers or breakfast in bed.

What I desire cannot be purchased or arranged.

I want someone to acknowledge my effort. How I manage to show up even when I’m very exhausted. How I manage to kiss their foreheads at night despite carrying the weight of invisible things like schedules, fears, and guilt. I want someone to say, “I see the woman you are, not just the mother you have become.”

Because I’m both.

A woman who once had aspirations that did not involve diaper bags or parent-teacher meetings. A woman who still longs for quiet mornings and uninterrupted thoughts. Also, a mother who has dedicated her body, sleep, and time to love so profound that it has utterly transformed her.

So, on Mother’s Day, I gave myself what the world frequently forgets to give: grace.

Grace for the things that remain undone.

Grace for the yelling I regret doing.

Grace for the dreams I’ve placed on hold.

Grace for the ways I am still learning to parent myself.

And maybe that’s all it needed.

Happy Belated Mother’s Day to the quiet mothers, the tired ones, the fierce ones. The ones who feel like they’re failing but keep showing up anyway.

I see you.

And I’m learning to see me, too.

Mother

They see

lunchboxes prepares,

schoolwork signed,

clothing neatly arranged into piles.

But they don’t see

the woman who forgot who she was

before responding to “Mama.”

They don’t see

how she holds her breath

until the door closes,

and she can cry

without needing to explain.

They don’t see

how she forgives herself

in small rituals—

a hot cup of tea,

a song in the car,

a scrawled poem

at midnight.

They don’t see

her saving herself

a little at a time.

And still

she shows up.

Every day.

with love nestled

into every nook of her weariness.

Because this is what she does.

That is who she is.

Copyright © Olivia JD 2025

All Rights Reserved.

✨ Looking for digital tools that support your everyday life with gentleness and intention?

At Olivia’s Atelier on Etsy, I offer more than just pretty printables—I create emotional support kits, Instagram reel templates, children’s meal planners, and other soul-nourishing resources for moms who give so much but rarely feel seen. Whether you need a moment to breathe, a tool to stay organized, or a way to connect with your audience—there’s something here for you.

🕊️ Everything is 50% off until June 2—because you deserve support that feels doable, beautiful, and kind.