After reading Susanna Jones’ novel The Earthquake Bird, I felt compelled to rewatch the 2019 Netflix adaptation. The film, directed by Wash Westmoreland and starring Alicia Vikander, Riley Keough, and Naoki Kobayashi, takes creative liberties with its source material while maintaining its dark, melancholic atmosphere. Despite some changes, I found the directors’ ability to capture the story’s haunting atmosphere impressive. However, the ending deviates radically from the book, providing viewers with the closure that the author purposefully denies. Despite the clean conclusion, I couldn’t help but believe that the book’s emotional ambiguity was more fitting. However, the film still provides an intriguing representation of Jones’ writing.

Watching it again provided me a new perspective on how the film adapted certain key components and departed from the original.

Image source

Lucy: A Different Lucy, A Different Background

The most noticeable distinction in the movie is Lucy’s nationality. Lucy Fly, the novel’s protagonist, is a British expat living in Tokyo. Lucy in the film is Swedish. Alicia Vikander’s portrayal of Lucy is captivating, capturing the character’s subdued and brooding qualities as envisioned in the book. That part seemed to be tailor-made for Vikander, who portrays Lucy as cold but fiercely vulnerable. She is the film’s foundation, and no one else could have played the character as convincingly.

Teiji: A Beautiful Mystery with a Dark Side

In the movie, Naoki Kobayashi plays Lucy’s love interest, the intriguing photographer Teiji Matsuda. Kobayashi’s Teiji is colder and more detached from the one in the book. His calm demeanor conceals a mild but unmistakable hostility, which adds tension to his interactions with Lucy. He is more indifferent to Lucy in the movie, which makes it plain that she is little more than a muse and a physical comfort to him. Where the novel’s Teiji shows glimmers of tenderness, the film removes those layers, exposing a man who is equally compelling and creepy.

The filmmakers altered Teiji’s backstory, having him raised by an aunt instead of his mother. This change adds a layer of mystery to his character, but it’s an easy element to overlook amid Teiji’s ambiguous personality.

Lily Bridges: A Scene-Stealer

Riley Keough as Lily Bridges steals the scene. Lily in the movie is flirty and outgoing but slightly needy. At one point, she even suggested she slept in between Teiji and Lucy, a moment that perfectly captures her brazen personality. Keough brings Lily to life in a way that matches how I envisioned her in the book: vibrant, needy, and ultimately tragic. Her presence adds a volatile energy to the story, and her dynamic with Lucy and Teiji is one of the more compelling aspects of the film.

A Cinematic Key Moments

The film’s cinematic storytelling enhances some passages from the book while layering the tension and beauty. One such moment comes when Lucy realizes that Teiji’s love has turned toward Lily during their time on Sado Island. The shift is slight but devastating, and the filmmakers pull it off with precision. The cinematography nicely captures Lucy’s mounting discomfort and the way it frames her isolation against the backdrop of Japan’s breathtaking landscape.

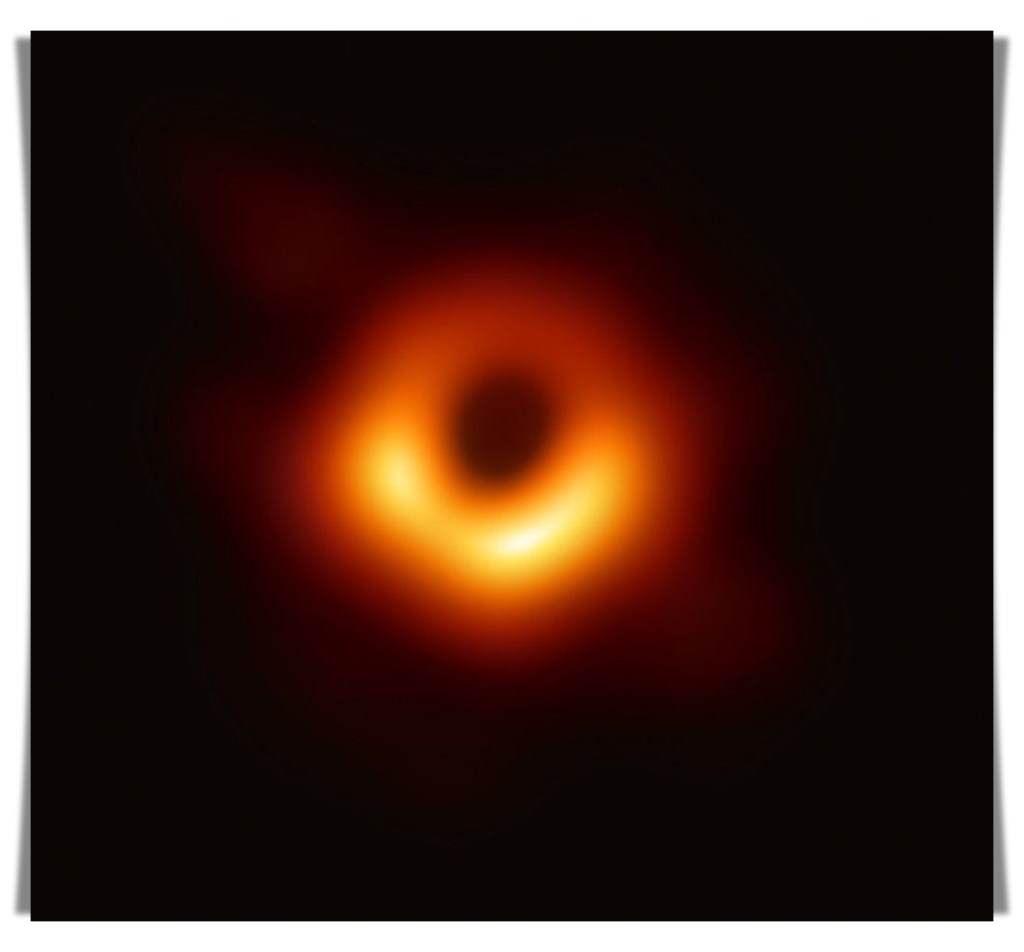

Image source

The other standout element in the film is Teiji’s apartment. Unlike the novel’s minimalist description, the film makes his living space a dingy and cluttered space mirroring his mysterious character. The apartment is almost a character in its own right, its junkyard atmosphere and eerie photographs lining the walls contributing to the film’s noir aesthetic.

The Earthquake Bird: A Haunting Force

One thing does get heightened in the movie: the titular “earthquake bird” reference. The bird is more vaguely referenced in the book, but the movie brings it to life, its haunting bird calls punctuating the moments of silence that follow an earthquake. That auditory detail adds another layer of unease, making the story’s themes of guilt and displacement all the more tangible.

Cinematography and the Haunting Soundtrack

The movie’s cinematography is breathtaking. It manages to capture the beauty of 80s Japan while also infusing it with a sense of foreboding. With such a subdued color palette and reserved framing, there’s even a noir-like feel to the film that works for its psychological aspects. Whether it is the bustling streets of Tokyo or the silent, windy fields of Sado Island, every shot seems meticulously crafted.

A special mention should also go to the haunting soundtrack. Composed by Atticus Ross, Leopold Ross, and Claudia Sarne, the music heightens the tension and melancholy of the story, settling into your head long after the last credits roll. It’s the kind of score that amplifies the emotional weight of every scene, transforming the movie into an immersive experience.

The Ending

The most significant departure from the book is the ending. The novel leaves a lot of questions unaddressed, requiring readers to contend with the ambiguity of Lucy’s guilt and the motives behind Teiji’s actions, but the movie prefers a more definite resolution. Without giving too much away, the movie does a good job of resolving some things and giving viewers a sense of closure. I admire the clarity, but I did find myself yearning for the unresolved tension of the book’s ending. That uncertainty seemed truer to the story’s themes.

Image source

Final Thoughts

The Earthquake Bird movie is a rich, visually deep, and emotionally haunting adaptation of Susanna Jones’s novel. While it diverges from the novel in some ways, it opens the story in new directions that could not have happened in the book. Alicia Vikander shines as Lucy. She succeeded in capturing the character’s multifaceted nature with ease and intensity. Naoki Kobayashi and Riley Keough deliver equally compelling performances. While some changes, such as Lucy’s nationality or Teiji’s backstory, seemed inconsequential, others, like the ending, significantly changed the tone of the story. The film’s portrayal of Teiji as a slightly colder character brought a darker edge to the story too. These differences notwithstanding, the movie stays true to the original novel’s exploration of guilt, obsession, and identity.

If you’ve read the book, the film is an intriguing reinterpretation of the story. If you haven’t, the film is still a tense and tight psychological thriller that stands on its own. Either way, it’s worth watching it for its breathtaking cinematography, haunting soundtrack, and outstanding performances. It felt like when I watched the movie, it was like a different perspective on the novel—familiar but different, unsettling but beautiful. It’s a story I’ll carry with me, in both its written and cinematic forms.